PHOTOGRAPHY

Jon Nicholson

WORDS

Lucy Frith

Hosted at Augustus Brandt within the majestic Grade II-listed Newlands House in Petworth, West Sussex, renowned photographer Jon Nicholson’s first-ever retrospective Pausing For Breath takes viewers on a whistle-stop tour of the world as seen through his eyes. From the conflict in Sudan, and the ranches of Texas, to behind the scenes at some of sport’s most thrilling moments, it is a captivating glimpse into 35 years of his work. Here, he gives Brummell an insight into his life behind the lens.

Selecting the images for the exhibition

How do you show 35 years in 100 pictures? The answer is you can’t really. So for Pausing for Breath, I’ve put up pictures that I like. They’ve all got interesting stories behind them – who I was photographing, what I was doing – they are all very personal to me.

Doing something different

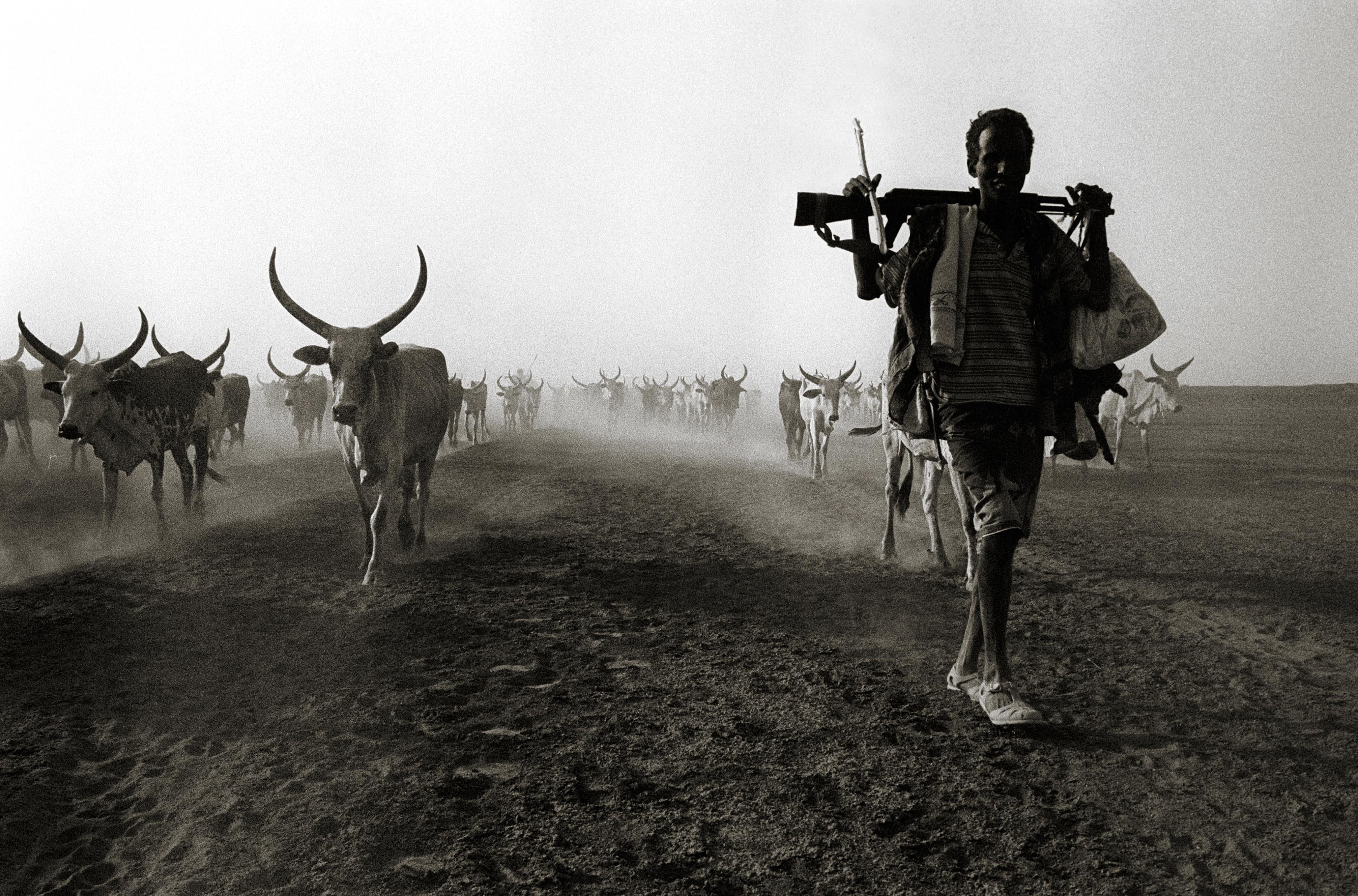

We’ve all got a slightly different way of communicating and bonding with people and things that we photograph. When I met photojournalist Don McCullin in 2006, he’d just got back from Chad where he’d been photographing refugees from Darfur in a way that had become the norm for images of conflict at the time. I decided I wanted to go to Darfur myself and photograph them in a way that is really going to capture people’s attention. I went over to New York, pitched the idea to the UN of doing huge prints – massive prints – of the feet of the ladies that had walked to freedom – these people have suffered rape, murder, everything. When people see the final image The Feet That Walked To Freedom, which is part of the exhibition, they say, ‘Wow, it’s so beautiful’, but you have to understand the story. And the story is hope. These people had suffered but they got away from it, they got saved. It is a beautiful, beautiful image.

Having an impact

I ended up doing a whole series of images for the UN, which was exhibited in New York and London. After they ran in The Sunday Times, George Clooney rang and he wanted to use the images on the site he founded with Matt Damon called Not on Our Watch, which raises awareness of conflict around the world. Then a lot of universities who were teaching about genocide wanted to use the images as they show a different side to genocide. That’s what I’ve always done; I’ve always tried to look at things in a slightly different way.

Keeping it together

When I’m in places like Darfur or Tibet, I have to focus on the job and it can be hard when I’m witnessing everything around me falling apart. A few years ago, I was working in Africa, I’d been there for a while and I received a happy birthday message from my daughter. It was the first time I’d managed to get signal on my phone since arriving. It really shocked me. When you get distracted by reality it kind of throws you off guard. At that moment I spotted a mother breastfeeding her twins and it had a real emotional connection for me. The picture I got, called Twins, is really powerful.

By that point I was already feeling quite emotional and I was due to fly home the next day. I suggested to the UN rep I was with that we headed to the local hospital. I was standing outside talking to a French doctor when this woman tapped me hard on the shoulder. When I turned she held out the severely malnourished child she was holding in her arms, willing me to take her picture. I took a couple of pictures and got in the car and said: ‘That’s it, I’m going home’.

Another time, I was in Liberia and there was this incredibly beautiful woman holding a child, I thought: ‘I need to get a picture of her’ so I went over to talk to her with a translator. But as we approached she handed her baby to me and ran. They had to get security to chase her and bring her back so she could take the child back. People see you as a saviour for their child. It really threw me and it made me think differently about how I take pictures.

Land of the Cowboy

One of the assignments that resonated with me the most was the Land of the Cowboy project. The way of the cowboy is vanishing, and it’s a massive shame because I grew up watching John Wayne and there’s a real warmth and depth in the day-to-day life of being a cowhand in the west. It took me five years to complete, and that involved many trips back to the ranches of southwestern America, where I made many friends along the way. I was able to explore the area and capture images of stuff you wouldn’t normally see, stuff that really intrigues. I was able to meet and stay with some amazing local families who have adapted to struggles with environmental and land use issues, low cattle prices and drought.

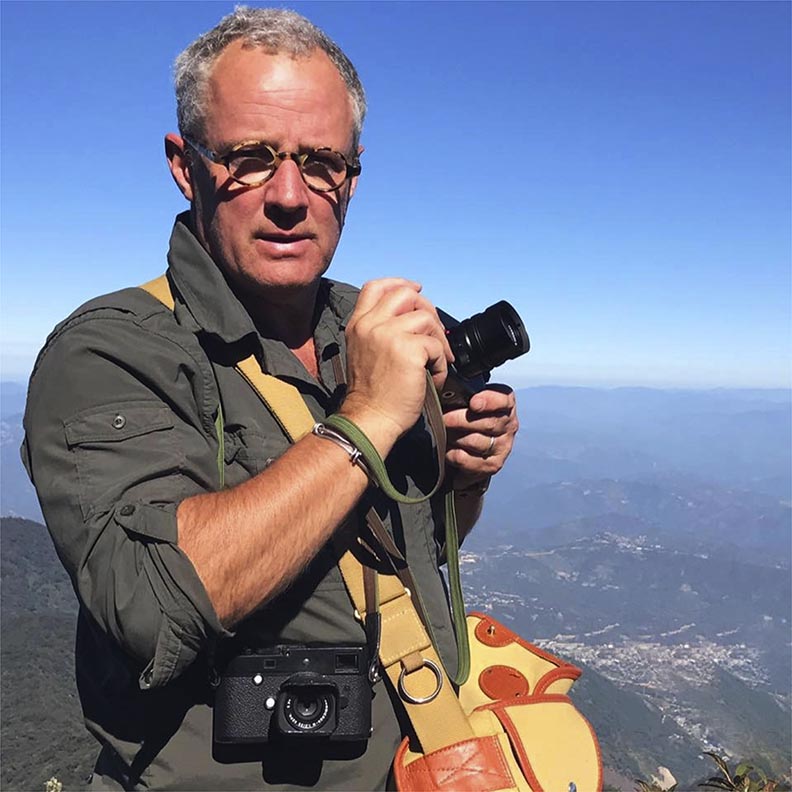

Building a rapport

One of the most important things you can do as a photographer is build a rapport with people. I have been back to visit people I have photographed many times to see how they are doing and how their stories have progressed. It’s about gaining people’s trust. I use a small Leica camera so most of the time I look more like a tourist than most tourists and can walk around quite freely without attracting attention. I would never shoot someone from across the street without talking to them first. I could be somewhere and there’s a woman selling pineapples who looks really interesting. I’ll go over and get a couple of pineapples, tell her what I’m doing and, eventually, she might offer me a drink and, in the time it takes to drink a cup of coffee, I need to have convinced her to let me into her life. Then she might introduce me to her husband who’s out the back cooking beans on toast for their 15 kids and there’s my picture. It’s about finding a shot, building a rapport, gaining access and potentially finding an even better shot.

Behind the scenes

One assignment that set me on the path for how I wanted to work behind the scenes in sport was with Linford Christie, when he was winter training with his team in Lanzarote in 1992. I knew the area well from my windsurfing days, and I had this vision of shooting him sprinting across the lava fields for The Mail on Sunday. He knew I was coming, but ignored me for the first two days. Then, on the third day, he invited me for dinner with his team and we chatted and had a laugh and I managed to get across my idea for the picture I wanted to take. He agreed and gave me 15 minutes. The next day, we got the shot, but he didn’t want to leave – he was so enthralled by this area he didn’t know was just outside his training camp. We sat and talked for ages.

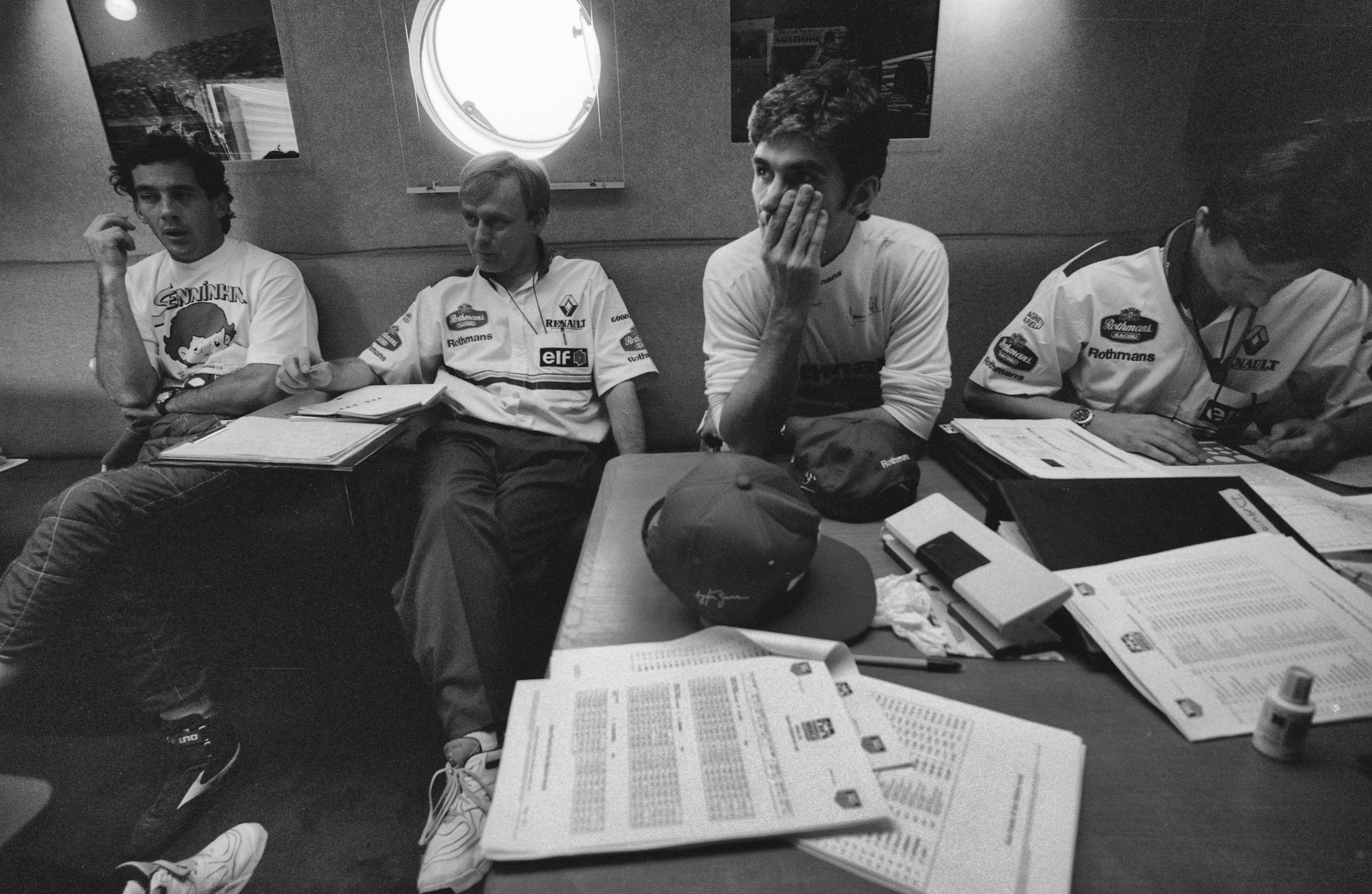

Ayrton Senna

One of the main reasons for me doing Pausing For Breath was to honour the 25th anniversary of Ayrton Senna’s death. This image (above), with Ayrton and Damon Hill, was taken in 1994, the morning after Ayrton’s best friend Roland Ratzenburger had died in a crash. Ayrton kept saying he didn’t want to race but it was business as usual. Then that afternoon, Ayrton himself died in the crash. This image (pictured below) sat in my drawer on a contact sheet for 24 years. I didn’t see it until the end of 2018, and at the time I didn’t think anything of it but when I scanned it, I looked at it and thought: ‘My God, the man’s already gone’. When you look at it, it makes you wonder: do people know they’re going to die? When you get involved in sport as a photographer, you don’t expect there to be death, you expect it to be happy. I put this up on Instagram soon after and I had a call from a guy in Italy saying, ‘I’ve just seen your post: how much?’ A lot of people tell me it’s the most beautiful image they’ve ever seen. That’s the interesting thing about Ayrton, he transcended racing and people remember where they were when he died.

The journey

In my 35 years as a photographer I’ve realised it’s about more than just photography, it’s about discovering something amazing about yourself along the way. When I was 24, I thought I was the best photographer in the whole world but I still had so much to learn. It’s great to have that enthusiasm but knowledge is also really important. I always had loads of big ideas and someone once said to me: ‘OK but if they say yes, can you actually do it?” and that’s the scary thing. I always have to make sure I can deliver – for every project and hopefully these pictures show that.

Pausing for Breath: A Retrospective by Jon Nicholson is at Augustus Brandt, Newlands House, Pound Street, Petworth GU28 until 10 August; augustusbrandt.co.uk; jonnicholson.co.uk