WORDS

Amy Raphael

Some time in 2003, two of the most influential people in the UK design scene met for a drink and wondered why London design didn’t have the collective voice it deserved in the way that, say, fashion has. Wine flowed. Sir John Sorrell, a leading figure in UK design, and Ben Evans CBE, a trained architect more curious about issues affecting design than practising it, decided there and then to create the design equivalent of London Fashion Week.

Evans rang Sorrell the next morning. ‘We had talked about so much stuff and I wanted to make sure we were both committed to getting this thing off the ground. So I asked John if we had actually agreed to try and start a London design festival He laughed and said, “Well, I think we did.”’

The first London Design Festival took place in various venues across London in September 2003 and, although Sorrell told the Financial Times that he was initially unsure whether it would fall flat, nearly everyone they approached agreed to participate. ‘I think “why not?” was the general answer,’ recalls Evans in his airy central London office. ‘We realised from day one that everyone wants new audiences, which is exactly what London Design Festival was offering. Of course we had to do a degree of arm twisting and cajoling, but it very quickly became a no brainer for most of them.’

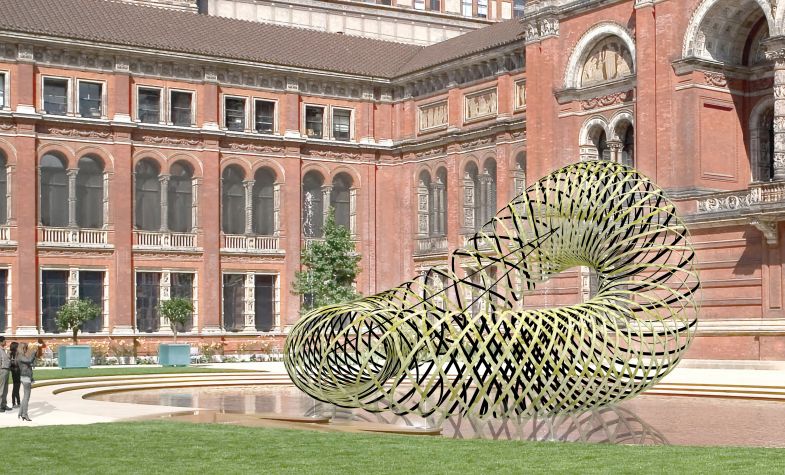

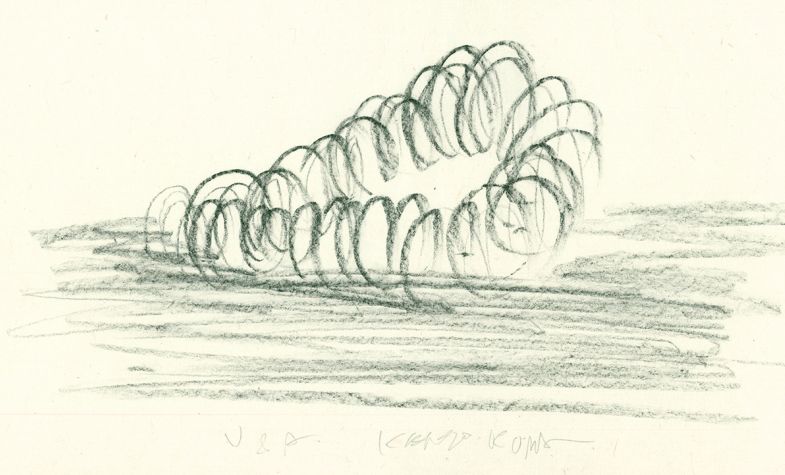

While Milan’s Salone del Mobile is, for example, a trade fair specifically showcasing the latest furniture design from around the world, London Design Festival is very much about the public engaging with design in 10 official design districts across the capital, both inside art institutions and in public places. This year Japanese architect Kengo Kuma has designed a large-scale bamboo installation in the John Madejski Garden at the V&A, and London-based design studio Patternity is addressing wellness and design with geometric black and white seating in Westminster Cathedral Piazza, called Life Labyrinth. The Shoreditch Design Triangle, the largest official design district in London, now hosts 60 independent events including Please Be Seated – a large-scale installation in Finsbury Avenue Square by Paul Cocksedge exploring the changing rhythm of the community.

Since 2003, London Design Festival has thrived and flourished to the extent that last year it boasted a record-breaking 588,000 direct visitors from over 75 countries over a nine-day period. That’s a lot of people. Evans smiles. ‘Prior to London Design Festival, a huge amount of design activity was unconnected and, as a result, was invisible to most audiences. Pulling all that activity together gave the design voice a much greater intensity than before. And, quite quickly, London’s status as a design destination grew. Big Italian brands started thinking, “Oh, there’s something going on in London, we’d better go and one, check it out and two, participate in it.” In that sense, we made an immediate impact. And London now has the biggest creative economy of any city in the world.’

This sentiment is echoed by the likes of Dr Tristram Hunt, director of the V&A, which acts as the festival’s hub; he refers to the festival as a celebration of ‘London’s role as the design capital of the world.’ Is this really the case, I ask Evans. ‘I am going to carry on saying we have the biggest creative economy until someone proves otherwise. There are 900,000 people working in the creative sector in London. Which other city has more?’ I concede that it’s an astonishing statistic. ‘It really is,’ says Evans, smiling broadly. ‘I was born in 1963 and I’ve seen the very beginnings of the creative industries expand to the point that we are a global city of creativity. It has happened quite organically. Remember this is a sector which the government only recognised 20 or so years ago, in the aftermath of the Blair victory in 1997, when there was the first attempt to actually map out the creative industries.’ He pauses. ‘But I’m worried about the moment we’re in, where the creative industries are going and what comes next.’

Ah, Brexit. The detrimental effect it will have upon the creative industries is unthinkable. ‘It is already having a detrimental effect,’ says Evans, his smile vanishing. ‘I hear people saying they went to a leaving party at the weekend. And the person leaving will be a young European creative returning to their country of origin, or moving to another European country to try their luck. It’s a bad sign, I think.’

The other big shift is, of course, towards sustainability. You only have to scroll down a design website like dezeen.com to see at one end of the scale, Central Saint Martin’s students creating toiletry bottles made from soap that can melt away when empty and, at the other, KLM making aviation more sustainable with V-shaped aircraft. This year, as well as a talk on the sustainability of bamboo, which releases 35 per cent more oxygen than trees, London Design Festival is working with the American Hardwood Export Council, whose website states that ‘American hardwoods are legal, sustainable and have low environmental impact’.

Sir John Sorrell, now chair of London Design Festival, has invited the leaders of 10 of the capital’s cultural institutions to create a “Legacy” piece of design using American red oak, which grows in abundance in hardwood forests. The pieces, which will be made by Benchmark Furniture in Berkshire, include some fascinating collaborations, including Kwame Kwei-Armah, artistic director of the Young Vic and Japanese designer Tomoko Azumi; Hans-Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, and Danish designers Studiomama, and Amanda Nevill CBE, CEO of the British Film Institute and London-based design studio Sebastian Cox (which already champions British woodlands).

Sorrell and Evans chose the pairings, with the notion not only of using sustainable wood but also of creating 10 legacy pieces which would have serious longevity. ‘Jasper [Morrison] has designed a low table and a pair of chairs for the meeting area outside Tristram Hunt’s office and it’s worth noting that the desk in the director’s office is still the one that was designed for Sir Henry Cole, the V&A’s first director, in the late 1850s. On that basis, people will be sitting on Jasper’s chairs, waiting for a meeting with the director, for at least another 100 years.’

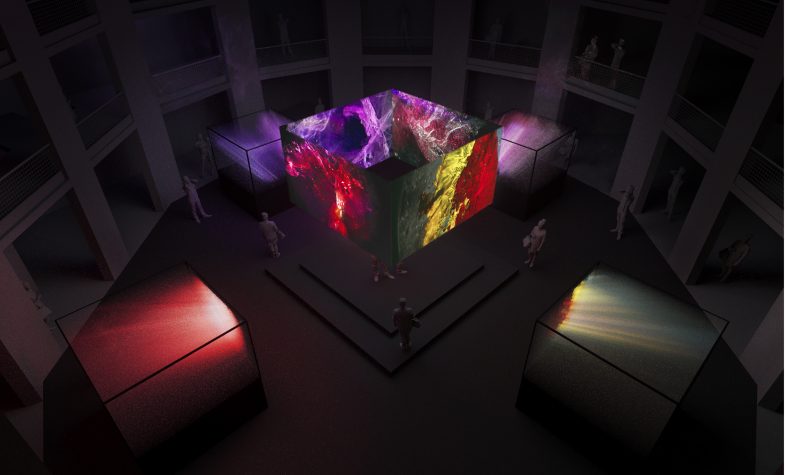

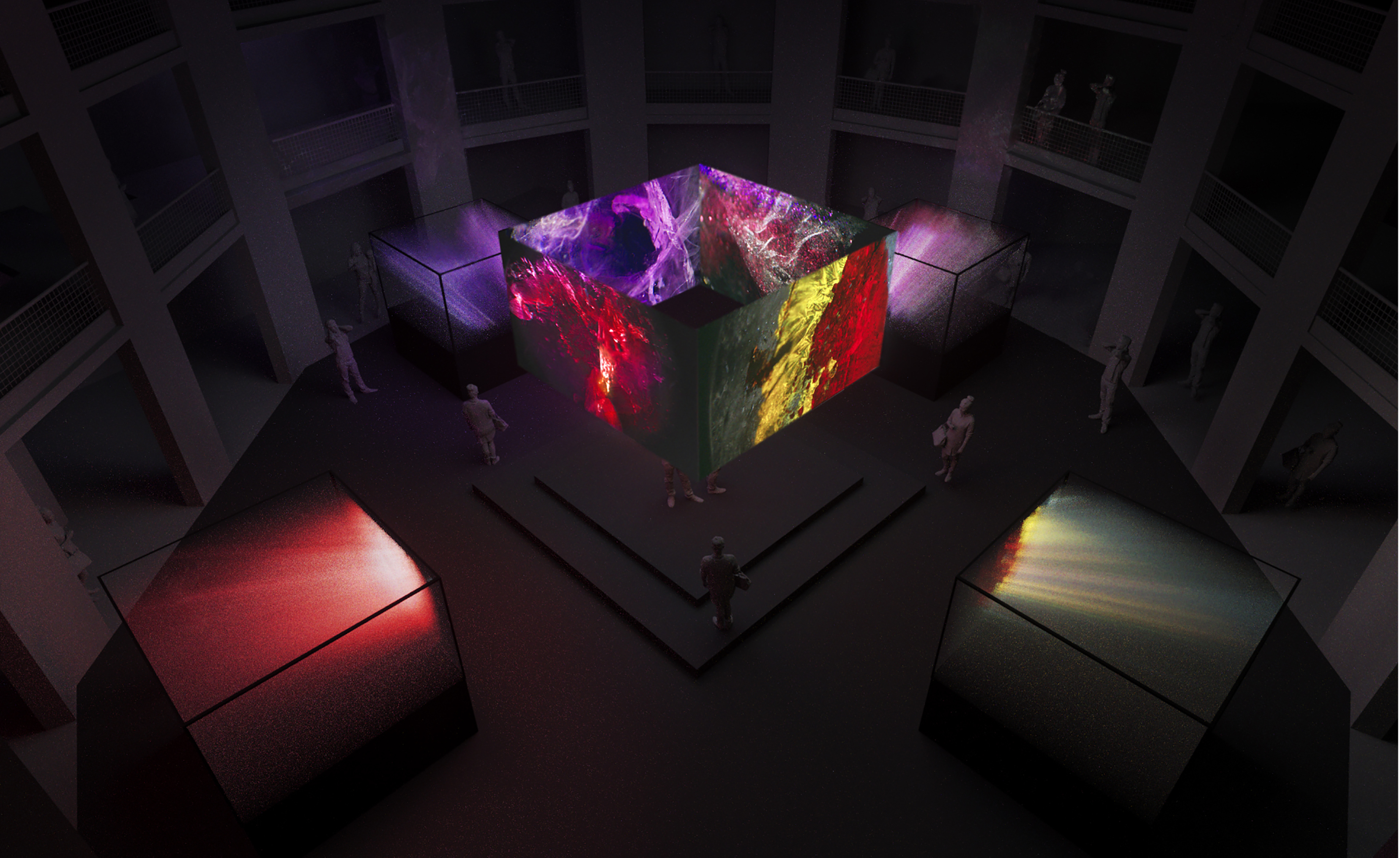

In the Prince Consort Gallery at the V&A, London Design Festival is looking not to the past but to the future. Sony Design’s Affinity In Autonomy is a pivoted arm which, Evans explains, ‘Will be curious about you. It’s very humanistic in how it tries to understand you and build a relationship with you. We have a very dystopian, sci-fi view of AI, but Sony is looking at the technology and seeing how, through design, it can change the relationship with the user.’

He says that Sony must become more than a lifestyle business and, as part of its evolution, rethink its relationship with its customers. ‘It’s looking at how technology can change the domestic environment; the obvious one is where you look out of the window and see any view you like, from anywhere in the world. How many of these experiments actually become services remains to be seen, but I think it’s an exciting direction for Sony. It has a bank of technology which it has to try and interpret in some way.’

When Evans was 15, his mother ‘dragged’ him away from the TV to a lecture being given by Richard Rogers about his experience of designing the Pompidou Centre with Renzo Piano. At Christmas that year, after a relative gave him Nikolaus Pevsner’s seminal 1936 book Pioneers of Modern Design, Evans realised he was at school with the great architectural historian’s grandson and shortly afterwards was invited to his Hampstead home for tea. That was it; he was seduced by design and resolved to study architecture. He still smiles like a kid when he talks about recent visits to California in which he was given exclusive access to the Eames House (‘it was built in 1949 and it’s a bit dusty; it needs the tender care of a well-funded foundation’) and Apple Park, the $5 billion circular building designed by Norman Foster for the corporate HQ of Apple (‘a pretty remarkable building, but for me it raised more questions than it answered’).

In the decades since he fell in love with design, Evans has witnessed the industry build and then explode in the UK, thanks, in part, to London Design Festival. ‘When John and I had the idea in 2003, there were perhaps four or five global cities with design showcases and events. Now there are at least 150 festivals, perhaps as many as 200, in cities across the world. We certainly had a head start because London is in the top two or three global cities in terms of design. And it’s important we stay there, at or at least near the top.’

Although he is resolutely a glass-half-full type, he points out that the ongoing impact of political uncertainty means the festival has another reason to exist these days. ‘It’s about keeping the balloon as inflated as possible. Keeping the profile of design up. Uncertain political times mean that London Design Festival is more vital than ever.’

London Design Festival runs at 11 venues across London from 14-22 September; londondesignfestival.com