WORDS

Peter Howarth

Rose Wylie doesn’t like people referring to her age or gender. Or her nationality. As she recently told Tim Marlow, the former artistic director of the Royal Academy of Arts, when he asked her about whether it meant anything to her to be referred to as an English, British or European artist: ‘It’s meaningless. I’m an artist.’

Marlow was interviewing Wylie at her home of more than 50 years, a 17th-century country cottage in Kent, which also houses her studio, crammed with paint and materials with newspaper strewn over the floor and canvases stapled to the walls. The place has the appearance of chaos, but it becomes apparent that it is really more to do with the freedom the artist craves – freedom to work with any influence or reference that takes her fancy. High culture and low, magazine images and old masters, the Renaissance and Disney. It is a truly eclectic vision and all the more remarkable because, though she doesn’t like people to make the point, Rose Wylie is 86 years old.

Marlow was speaking to Wylie as part of the preparations for the new exhibition that recently opened at The Gallery at Windsor, Florida, of Wylie’s work. Called Let it Settle, it is the third collaborative exhibition in a three-year series The Gallery at Windsor has put on in association with the Royal Academy of Arts. The Gallery at Windsor lies at the heart of Windsor, the private residential community built by W. Galen Weston and the Hon. Hilary M. Weston in Vero Beach, Florida, which they started in 1989. The Gallery opened in 2002 and has shown work by a whole host of acclaimed artists, including Peter Doig, Ed Ruscha, Jasper Johns, Christo & Jeanne-Claude and Christopher Le Brun. The previous two Royal Academicians hosted there as part of the partnership with the Royal Academy were Grayson Perry and Michael Craig-Martin. And this year, the final exhibition in the series sees Wylie’s work make the trip to Florida.

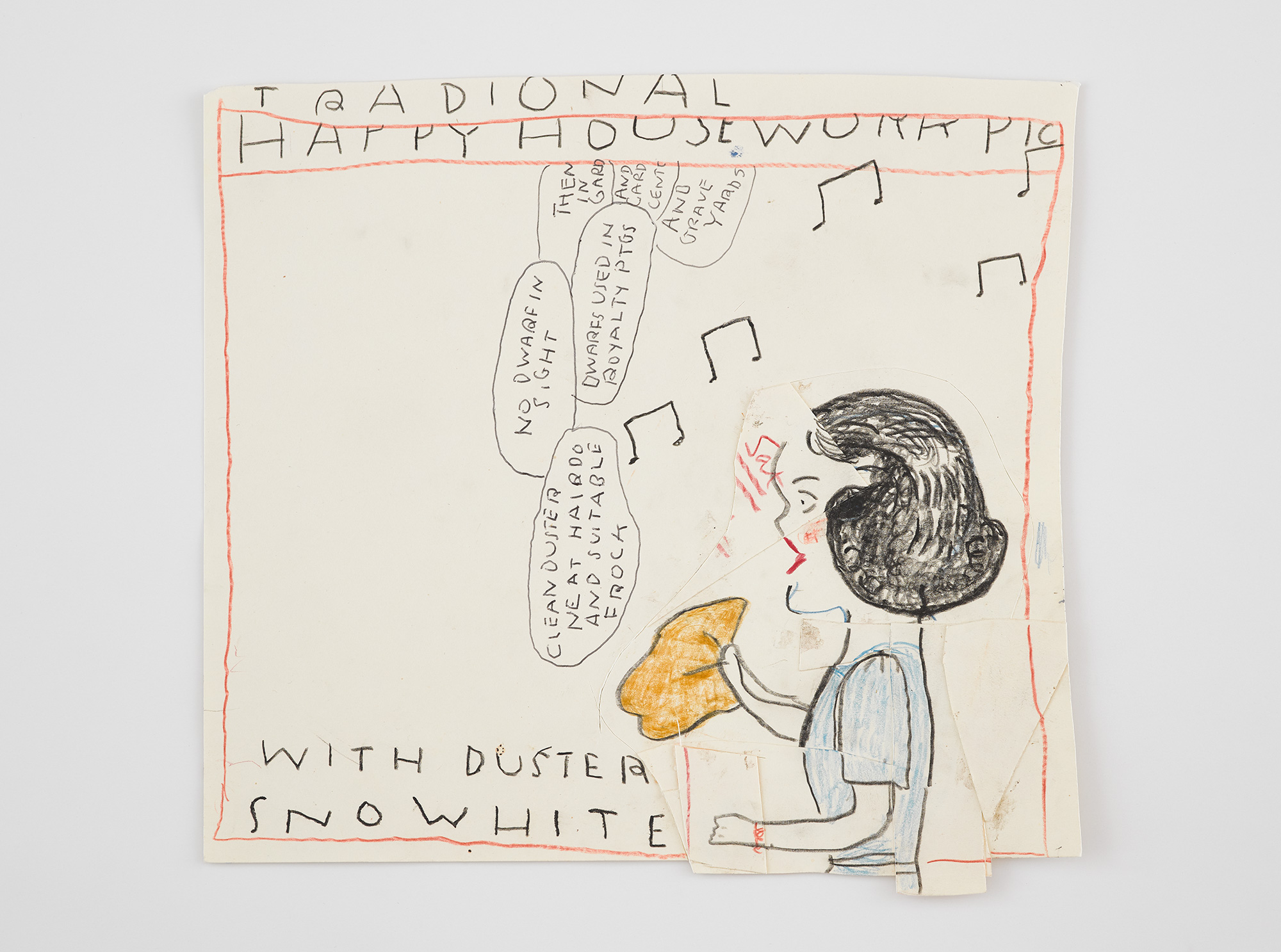

Exploring themes of Britishness, monarchy, fairy tales and popular culture, Let it Settle contains works on canvas and paper. Wylie’s technique is to make working drawings that then sometimes form the basis of large paintings. Using collage, text, and a free painting style that is beguilingly and deceptively naive, she creates works that are fresh and witty, and reward proper consideration. A group about Snow White, for example, with the repeated motif ‘Someday my prince will come’ refers not only to the Disney film that Wylie was terrified by when she saw it at age four, but also ideas of domesticity, marriage and feminism. A drawing in the room inspired by David Hockney name checks the British royal family, and in another room there is a large canvas called Elizabeth & Henry with a massive representation of Rochester Castle. We are in the realm here of a real historical royal dynasty, where the Snow White story of a girl waiting to be rescued by marriage to a prince takes on new meaning. In the context of recent events in the house of Windsor, the work takes on powerful new meaning, and you cannot help think that Wylie’s choice of pictures to exhibit here was influenced by the fact that the gallery is in another Windsor, albeit one in Florida.

The Gallery at Windsor was founded in 2002 by Alannah Weston, daughter of Galen and Hilary, and now chair of Selfridges Group. Hilary is The Gallery’s creative director. ‘I have long admired the creative energy in Rose’s work,’ she says and recalls how she, like Marlow, visited the artist at the home that doubles as her studio. ‘When you see the scale of her work in situ it is most impressive,’ says Hilary. ‘She cuts her canvas to the maximum dimensions of her walls, and manoeuvres the panels in this enclosed space on the first floor of an ancient house, to create multiple-panel paintings.’

The finished pieces on show in the exhibition are indeed large and impressive. But they also manage to preserve the spontaneous look of the sketches and works on paper that are exhibited by their sides. Russell Tovey, the actor, who is a keen art buff and runs a podcast called Talk Art, has written an eloquent appreciation of the artist in the exhibition catalogue. Here he zeros-in on this spontaneity, which is the result of an approach that seems to have the uninhibited enthusiasm most often associated with children: ‘Crazy beautiful free associations, unbiased and without rules as to who, where or when, are the fundamentals of Rose’s work,’ he observes. ‘A cast of strangers loosely choreographed into performative motifs. We find her characters in totally unexpected situations, guided by an artist passionately inspired by a love of cinema. Scenes framed like movie stills are mined again and again for the perfect shot from a multitude of angles – from the extreme close-up to the faraway wide. Her works live on the surface, but they are never flat.’ Picasso famously said: ‘Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.’ Rose Wylie seems to have solved that particular conundrum.

Talking to Marlow at the opening in Florida, he made the point that Rose Wylie’s work has an immediately identifiable appearance, characterised by the interconnectedness of her references and subject matter. He calls it a ‘rhizomatic’ approach, where ‘there’s a whole network of things that are not apparently connected, but which are all under the surface.’ This is part of Rose Wylie’s magical appeal. The Queen of Sheba and Chelsea footballer John Terry meet, Choco Leibnitz chocolates and Quentin Tarantino are of equal value to her as 17th-century monarchy painter Robert Peake, or Philip Guston, who is an acknowledged favourite. As is, indeed, cave painting. As Wylie said to Marlow in their interview: ‘Time doesn’t matter. Country, race, doesn’t matter.’

This amalgamation of images and references in some way mirrors our daily experience, where memory, the present moment, and the worlds of advertising, art, fashion, sport and film all collide. Wylie is aware of this. She told Marlow, speaking of her influences: ‘It can be Rilke, or it can be that bloke Giovanni di Paolo; it can be a journey I made to meet someone and saw that person on the train. They come together. But then, don’t you think that’s what life is like? We meet.’

Let it Settle runs until 30 April 2020. To visit, contact The Gallery at Windsor through windsorflorida.com/gallery.