WORDS

Robin Swithinbank

As a rule, octogenarians have to be handled with care. You hold doors for them, carry their suitcases, encourage them to sit down while you make the tea. Gary Player, the 83-year-old golf legend, is having none of it. ‘Look at guys my age – they can’t walk!’ he cries. ‘I can put my feet above my head. Watch.’ And with that, he jumps up and does the sort of cancan high-kick that would break a man half his age (me). He may only be five-and-a-half feet tall, but yes, Gary Player can still get his feet up above his head.

Player – who along with Chip Beck must surely hold the title of greatest ever name for a golfer – was always obsessive about his regime. Nicknamed Mr Fitness back in the day, he took a scientific approach to exercise, weight training, diet and sleep, as well as hitting balls for hours on end as a means to winning more. ‘The more I practise, the luckier I get,’ he once said.

It worked. According to golf statistics, he is fourth on the all-time list of major wins with nine, and has won 167 tournaments around the world since turning professional aged 17. He’s also one of only five golfers and the only nonAmerican to win the career Grand Slam, scooping all four of golf’s majors at one time or another.

He did all this despite being diminutive by golf ’s standards, hailing from a poor background, and having to travel to tournaments from his home in South Africa at a time when transcontinental aircraft travel was at its most exhausting. He’s spent his life on the road, chasing victory (he’s also bred more than 2,000 race-winning horses), racking up so many air miles he believes he’s travelled further than anyone in history.

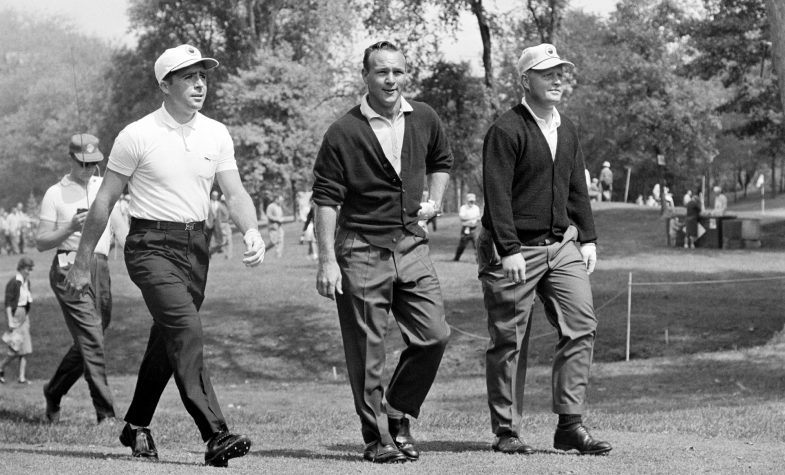

His successes also came during an era otherwise dominated by the Americans, Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer not least among them. To say that he was disciplined would be an understatement. He had an animalistic sense of competitiveness and a resolve you could douse in turpentine without fear of it dissolving.

‘I think success is an accumulation of a lot of things,’ he says, when prompted to explain his own. ‘You’ve got to have a lot of love in your heart. You’ve got to do a lot of hard work. And obviously, you’ve got to have talent.’

Player certainly had talent. He didn’t pick up a club until he was 14, his gold-mining father scraping together a loan to buy him his first set, and then, as legend has it, parred the first three holes he played. Easy game. Three years later, he was making a living from it. In 1959, aged just 23, he landed his first major, picking up the princely sum of £1,000 for winning The Open at Muirfield, Scotland.

Sixty years on, he thinks there’s more to winning than guts and glory. ‘You have to be grateful for the opportunity and to take advantage of it,’ he says earnestly, remembering that he missed the birth of his first child to be in Scotland that year. ‘People now have a tremendous sense of entitlement, but a sense of entitlement is a danger. If you look at all the best boxers, they came from poor homes and rough areas. They had nothing. They had to survive.

He warms to his theme. ‘I talk to young people in America and I say: “Who wants to be a pro?” Everybody puts their hand up. I say: “You’ve got no chance!” They wake up in the morning, they have breakfast with their mommy, they’ve got a car, air-conditioning, three meals a day.’

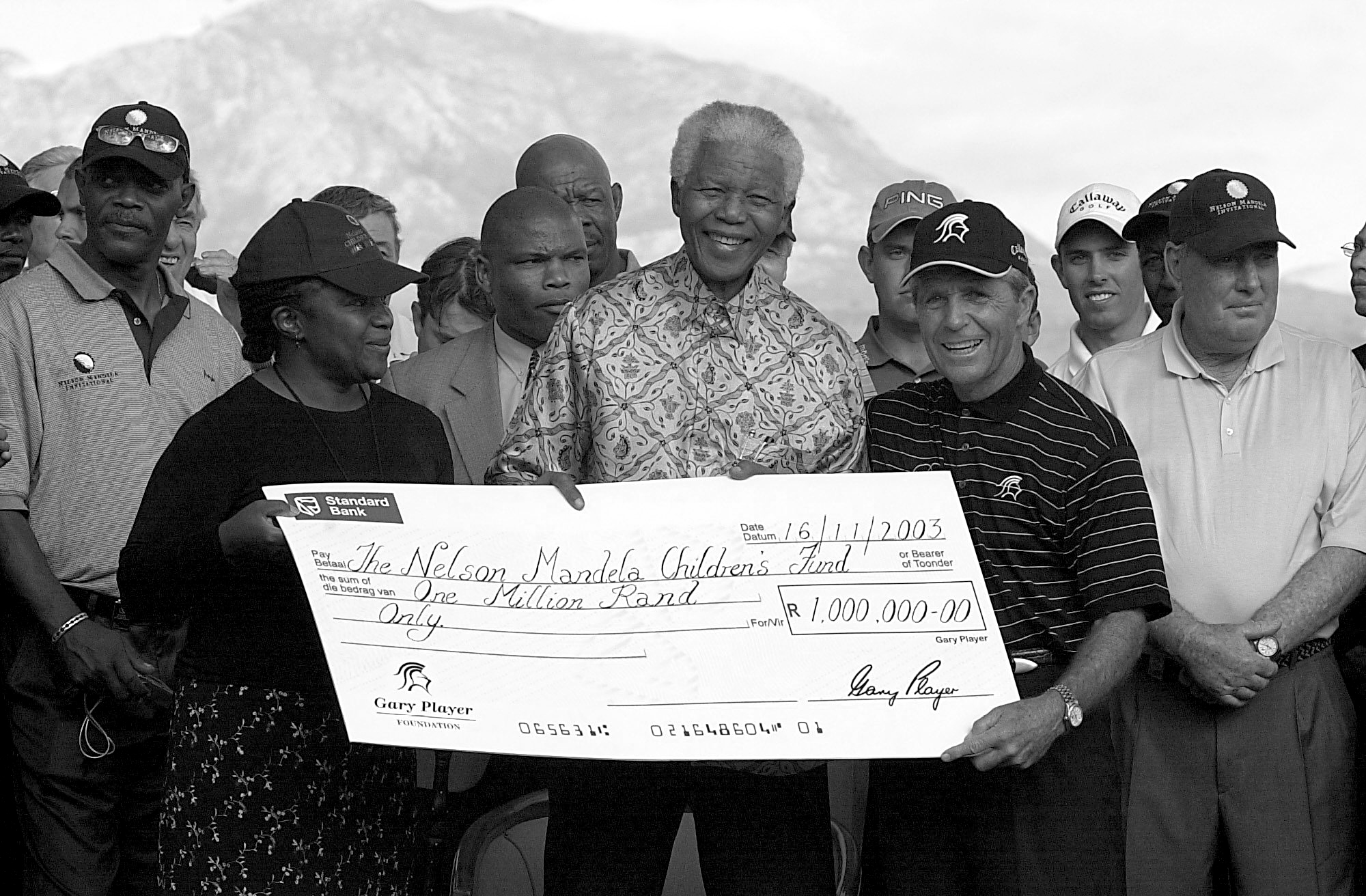

Player’s mother died when he was eight years old. He grew up with little and has spent much of his adult life fighting for those with even less. He’s a long-time supporter of the anti-apartheid movement, befriending and advocating on behalf of Nelson Mandela (with whom he later became friends – ‘When I met Mandela, he said: “Thank you very much.”’), and famously wearing black and white trousers at the 1960 Open Championship in protest at his own government’s adoption of the system of segregation that defined South Africa for more than 40 years.

Today, the Player Foundation continues to raise money to help lift children out of poverty. Largely using golf as the mechanism, he says the foundation has raised $64m, partnering with the likes of Germany’s Berenberg Bank. ‘In China we built houses for the Aids children,’ he says. ‘In South Africa we built two schools. We want to do something for homeless people. These same people who were sleeping in the streets are becoming doctors and lawyers. Isn’t that great?’

There’s a sort of sad sparkle in his eyes as he says this, real emotion bursting through his clipped tones. He seems unhappy that the world isn’t working better, but overjoyed that he’s been able to play a part in doing something about it. ‘I don’t like to tell people about my problems, because we all have them,’ he says. ‘But I had terrible years. It’s about gratitude and respect and love of people.

He is a man of faith, which he says has driven his philanthropy, and also helps him ‘to rectify my faults’ and ‘to say sorry’. He goes back to Mandela, another man of faith. ‘We all make mistakes and we must all learn to forgive,’ he says. ‘Nelson Mandela went to jail for 27 years for doing the right thing, and yet he came out and forgave them. Can you imagine? I said: “You must hate the white man!” And he said: “I don’t hate anyone. If I’m like an apple that’s green on the outside and rotten on the inside, I can’t get people to work together, I can’t unite the country.” He was a phenomenal man.’

Our chat has come to an end and Player has to go… to the gym. What else would a man on the cusp of his 84th birthday be doing at 5pm?