WORDS

Tony Chambers

I first met Paul Smith when I was a designer in the art department at The Sunday Times, but it was a couple of years later that I really bonded with him. By then I was art director of GQ magazine, and we were shooting his friend David Bowie. Paul had designed a collection inspired by Hunky Dory-period Bowie, because for the original album he had made the singer’s wide-legged trousers. I remember that what Paul brought to that day in a London photographic studio, apart from some memorably patterned and coloured clothes of course, was a real sense of playfulness. He and I were big Bowie fans, so we were having fun, but Paul’s energy was palpable. One moment in particular stands out: during one set-up he photobombed, sticking his head around the backdrop. We used the image in the magazine as it so perfectly captured the friendship of these two British creatives.

Years later, I received a package from Paul containing a T-shirt and a note. It said “David asked me to make some of these for him, I hope you like it.” It was for Blackstar, which was to be Bowie’s last album. That’s typical of Paul – keeping in touch with a handwritten note and a generous gesture.

This year, I have put together a book to celebrate Paul Smith’s 50th anniversary as a designer and I have discovered that there are many people out there with similar notes, similar stories – recipients of thoughtful gifts from the man, or, more importantly, of his time, advice and help. Speaking personally, I can say that he has been supportive of my entire career; without any hidden agenda he has offered inspiration, just wanting to pass on his knowledge and experience. When I became editor of Wallpaper he put together a selection of lovely books and reference materials for me that I might find useful. He is genuinely interested and passionate about the worlds of creativity and communication.

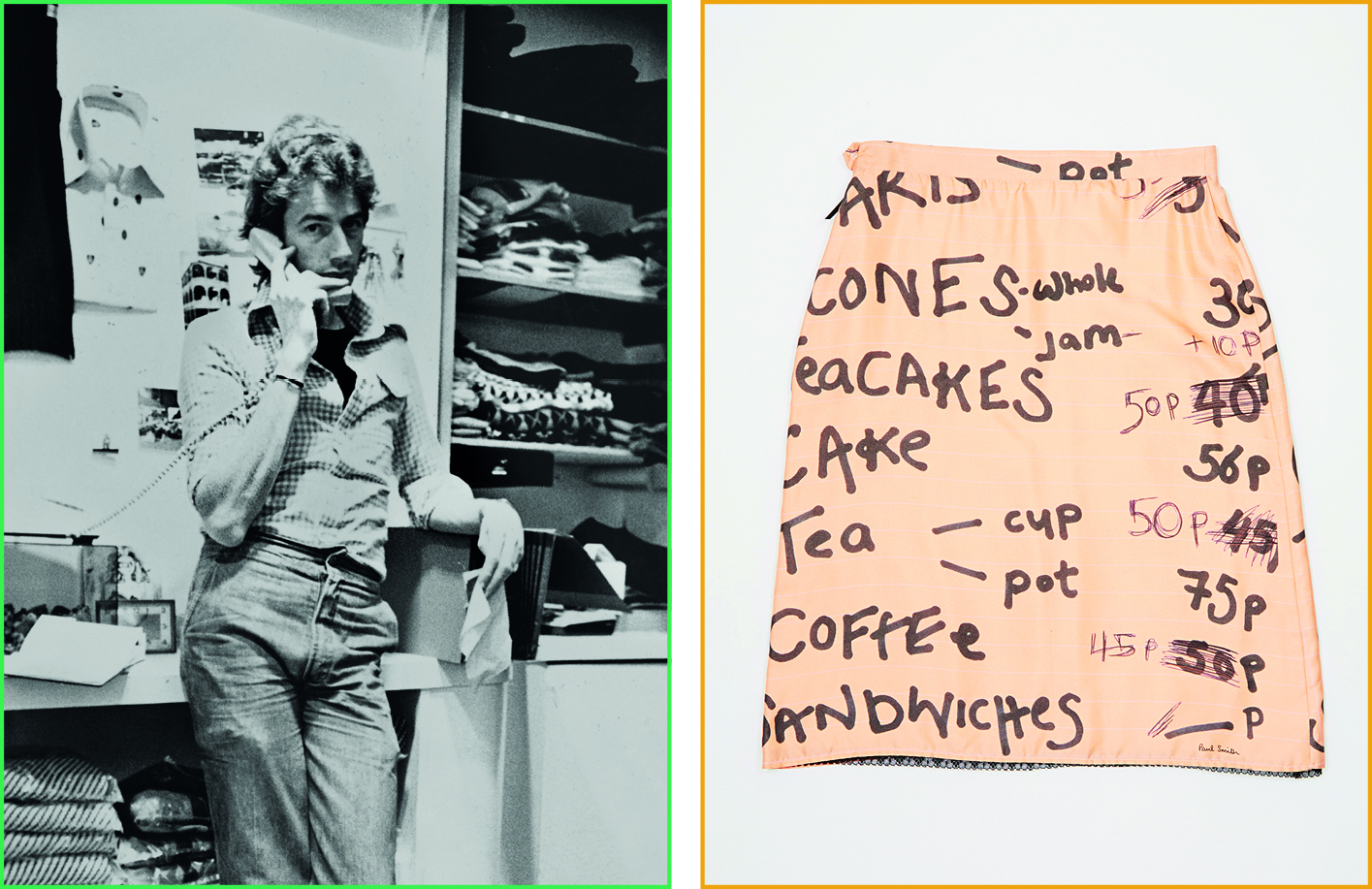

It was back in 1970 that he opened a 12 sq ft windowless room on the first floor of a building in Nottingham where he started to sell pieces of clothing he’d had made, assisted by his Afghan hound Homer (who smelled so much his owner had to spray Dior Eau Sauvage around). Today, he is a knight of the realm and presides over a fashion empire, still selling clothes, still shop keeping, still going strong. How has he done it?

For the book, I decided to ask a whole host of people – fashion industry insiders, journalists, celebrities, architects, musicians, you name it – to answer that question: what is it about Paul Smith that has such winning appeal, and why has it endured so well? What I discovered was that I was pushing against an open door. The man is much loved. Nobody I approached refused to contribute; all have done so with a degree of warmth that speaks of genuine affection.

I had my own theories, of course. Paul Smith, brand and man, are inextricably linked. He’s an absolute grafter, and anybody who succeeds has to be. Then, he has endless creative drive and curiosity at a level nobody can hold a flame to – I’ve never met anybody with his level of boundless enthusiasm for ideas. He says he’s childlike not childish, and, like Picasso who spent his entire career trying to recapture the innocent spirit of drawing and art making he had as a kid, Paul has resisted becoming a cynical grown-up and being inhibited by maturity.

This translates into the work, of course – whether it’s making a printed shirt, or a coloured pair of shoes, or opening a store in an old café on the Parisian Left Bank and leaving the original fittings in situ. What he has done for fashion, and for men particularly, is to democratise it and make it inclusive for all. He’s shown people who were maybe only comfortable in suits and tailoring that they can dress down and perhaps feel more like themselves, and conversely, he has given people who are only comfortable in casual attire permission to dress up.

The contributors to my book have borne out my hunches, but also added so much more. Through their comments I have come to understand that Paul Smith is all about personality, which is what consumers crave. And that he has instinctively been doing for years what business gurus now describe as “design-thinking” and “customer empathy” – in other words, he’s been thinking laterally and creatively (like a designer) about his business, and routinely still works in his Mayfair store on a Saturday to meet the people who shop there. He’d hate to think he was an example of current business and marketing theory best-practice, but he is. In a completely authentic and uncontrived way.

That’s why he is still relevant and still being worn by people who were not even born when he first started his label in 1970. Plus, as did his friend David Bowie, he has been able to reinvent himself time and time again for each successive decade.

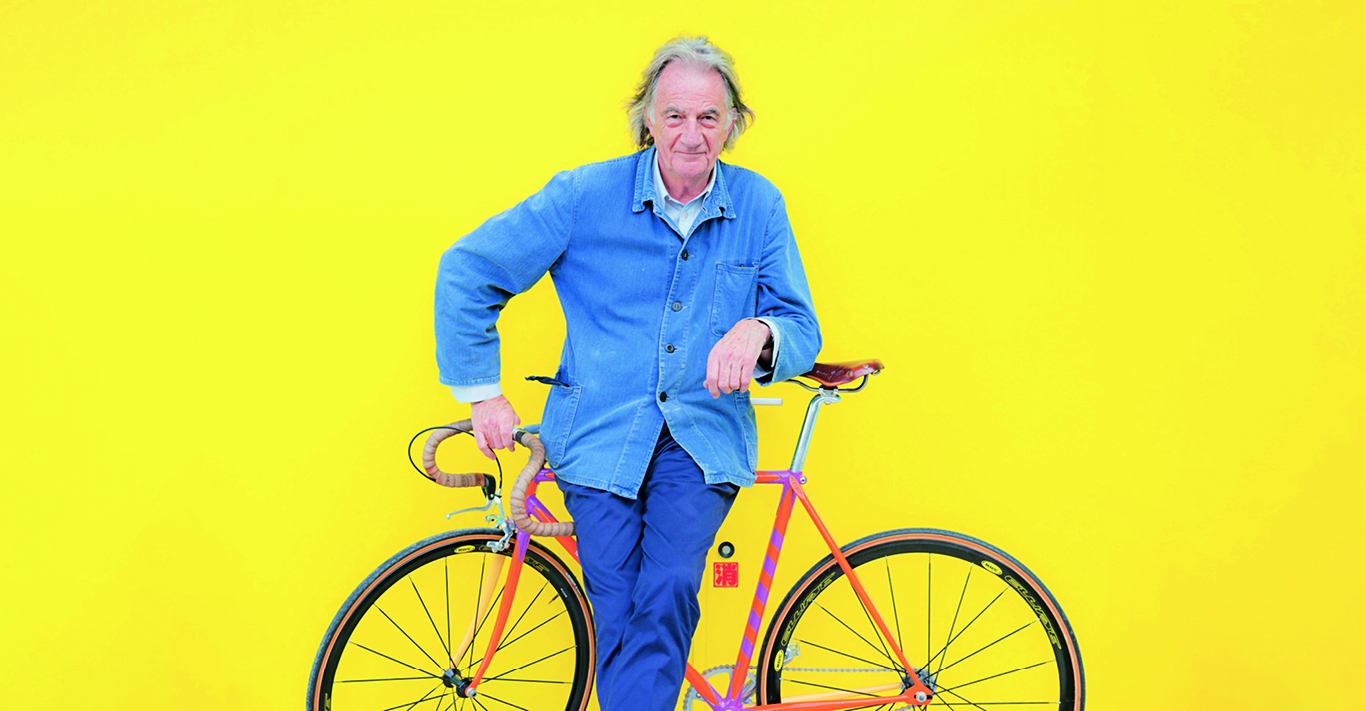

I’ll leave the last word to Ines de La Fressange – model, fashion designer and perfumer, who sent me this for the book, which I can’t improve on: “Sir Paul Smith is a bunny on a bike on a marvellous striped and coloured road. He is a workaholic who loves his wife, he will never be a bourgeois and understands elegance doesn’t have to be uptight. For me, he is the symbol of what is the best in England.”

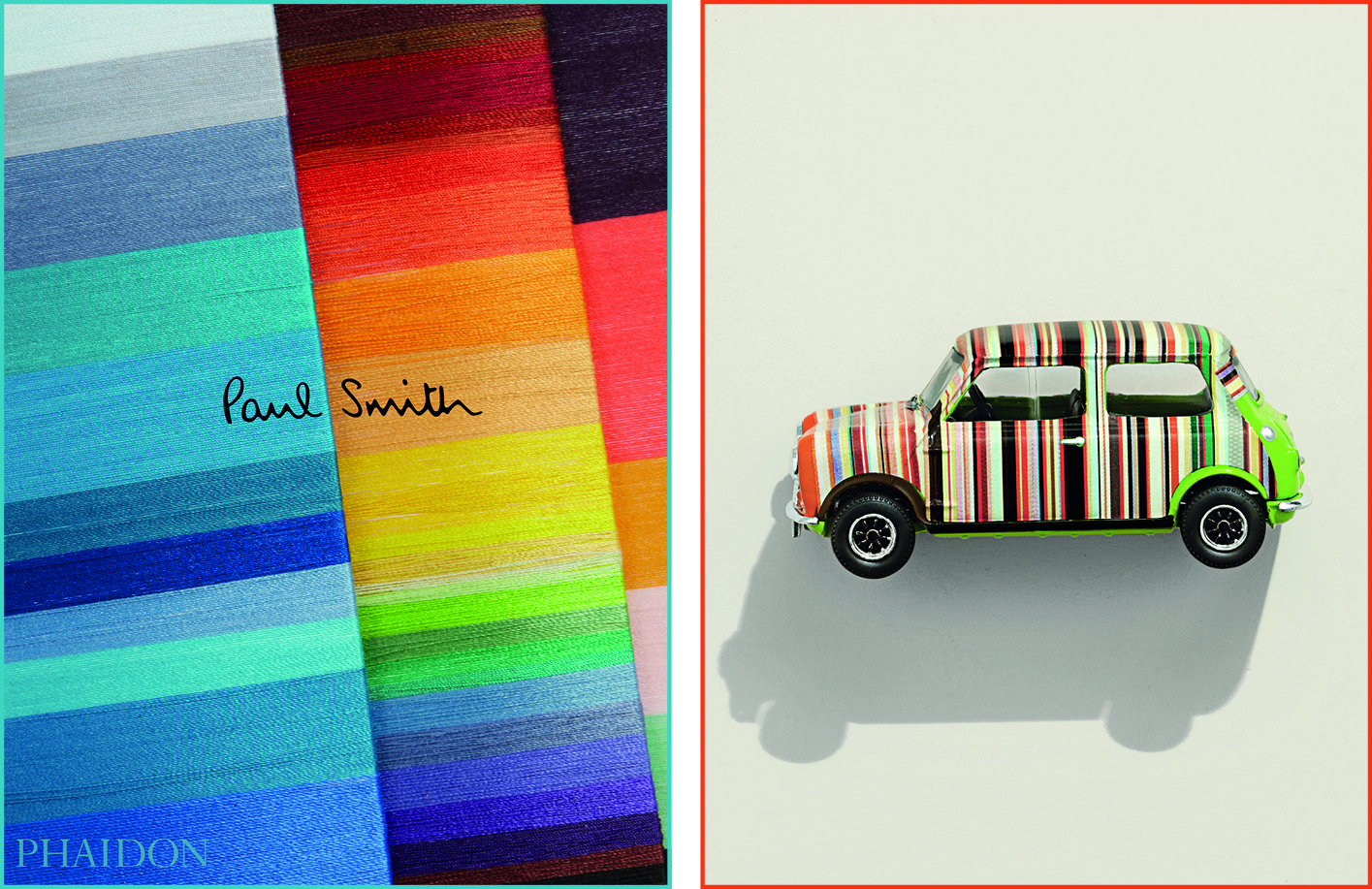

Paul Smith, edited by Tony Chambers is published by Phaidon, £49.95; paulsmith.com