WORDS

Chris Madigan

The story of many a Scotch whisky distillery is one of rise and fall and rise from the dead. Often more than once. One that we should be most relieved that someone got to defibrillator in time for is Benromach. The Speyside distillery was mothballed in 1983, one of many United Distillers locations which stopped production. A decade later, it was the first distillery bought by independent bottler Gordon & MacPhail.

The smallest working Speyside distillery returned to action in 1998, but not trying to carry on where the old distillery left off. Distillery manager Keith Cruickshank, who was second-in-command at that time before taking the helm two years later, explains: ‘Benromach wasn’t really producing a single malt in the 1980s; it was producing juice to serve blenders’ requirements. So, we had a blank canvas. We decided to reintroduce a lost Speyside style. We looked back at Gordon & MacPhail bottlings from the 1950s and 1960s of Glenlivet, Strathisla, Longmorn, Glen Grant, Mortlach. And we also had new-make samples of these, because G&M would buy new-make and bottle it 12 or so years later.

‘What we found was a theme: full-bodied, medium to heavy-style whiskies; sherry-influenced, yes, but lovely malty notes and, the most distinguishing note, a lovely, elegant smokiness.’

That smokiness is a welcome addition (or reintroduction) to Speyside whiskies. It’s not the medicinal, iodine, barbecued sardine reek of Islay peated malts. It’s an autumnal bonfire or fireside smoke that subtly weaves around fruit, flower and baking notes.

‘We had to take decisions at every stage of our process – the light peating level of the barley; using brewer’s yeast as well as distiller’s yeast for that maltiness; extended fermentation but a cloudy wort; long, cool distillation; and we had to temper the stills for six months because the new copper was producing too bright a spirit to begin with,’ says Cruickshank.

The “new” Benromach has been operational for over two decades now, so there have been releases up to 21YO of the re-found Speyside style, as well as remarkable experiments in extra peat, virgin oak or wine finishes. Still, its production of 200,000 litres a year is a pipetteful in comparison to Glenfiddich’s 21,000,000lpa.

At the same time that Gordon & MacPhail rescued the distillery, it also acquired the old stock, moving it to its warehouses in Elgin. The king of indie bottlers recently announced it would no longer buy new-make spirit from other distilleries; the company has built a new distillery near Grantown-on-Spey, the Cairn, in addition to Benromach. However, the inventory G&M already has will keep it in bottlings for decades to come.

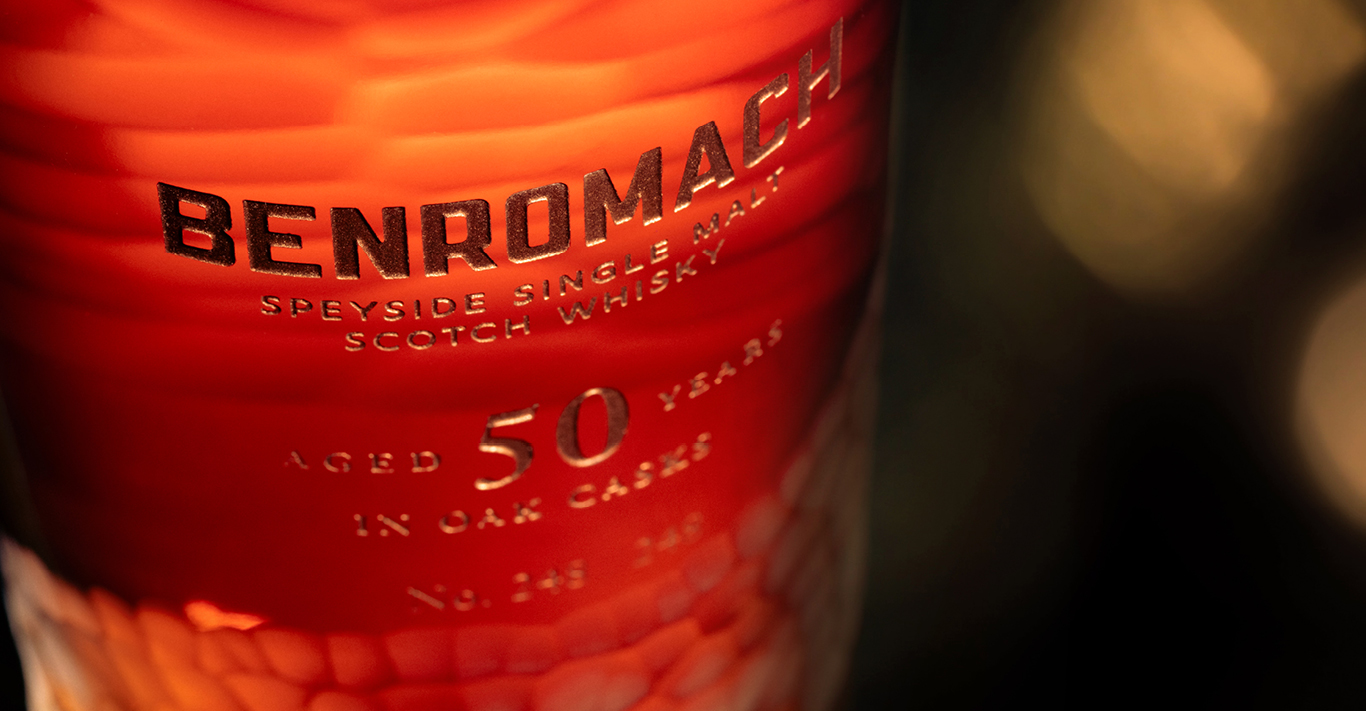

One of the Benromach casks that was maturing nicely in Elgin was distilled in 1972. It has now been released as Benromach Aged 50 Years and is a revelation. It has a floral perfume woven with freshly sawn wood, leather and fruit crumble, before a series of different fruit explosions in the mouth – fresh strawberry here, stewed fruit there, orange zest over yonder – with gentle firewood smoke drifting over it. In this instance, that smoke is more likely acquired from the heavily charred cask than from the barley, which was unlikely to have been peated at that time.

There are 248 decanters (£20,000), each marked individually by battuto detailing, handcrafted by Glasstorm, a hot glass studio in Tain, also up by the Moray Firth, near Elgin.

So, what does Keith Cruickshank think has changed in whisky since this liquid was distilled 50 years ago and how he works now? As romantic as whisky marketing would have us believe whisky making is, Cruickshank says that the biggest differences are in technology and science and how they affect the flavour of whisky.

‘Fifty years ago, you did it in a certain way because you knew that was the best way to do it, but they didn’t fully understand the why or how you control those flavours. There’s a lot more known about the flavours and compounds in the new-make spirit, which is the DNA of the whisky.’

Marketing departments across Scotland can breathe a sigh of relief though: ‘What are less understood are the variables in maturation. Yes, we understand the different effects of American white oak and European oak, or the interaction with different charring levels, but there’s so much that goes on there that we’ll never understand, and it’s great because it’s that mystique which will always keep Scotch malt whisky interesting to drinkers throughout the world.’