Fifty years ago, on 16 July, the Apollo 11 spacecraft lifted off from Kennedy Space Centre in Florida with a three-man crew. On 20 July, the craft landed on the moon and two of its crew became the first men to set foot on the moon. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, we are speaking to a different astronaut every day to find out just what it takes to make it to outer space.

Charlie Duke was capsule communicator (CapCom) on the Apollo 11 mission, so it is his voice you hear speaking to the astronauts in space. He got to go to the moon himself in 1972 as lunar module pilot for Apollo 16. He is the 10th (out of 12) and youngest person to walk on the moon.

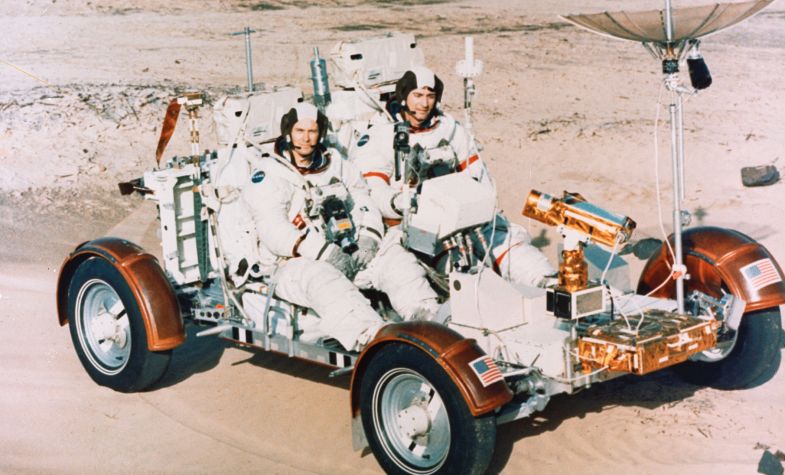

Credit: Apollo Photo Archive Collection/Alamy

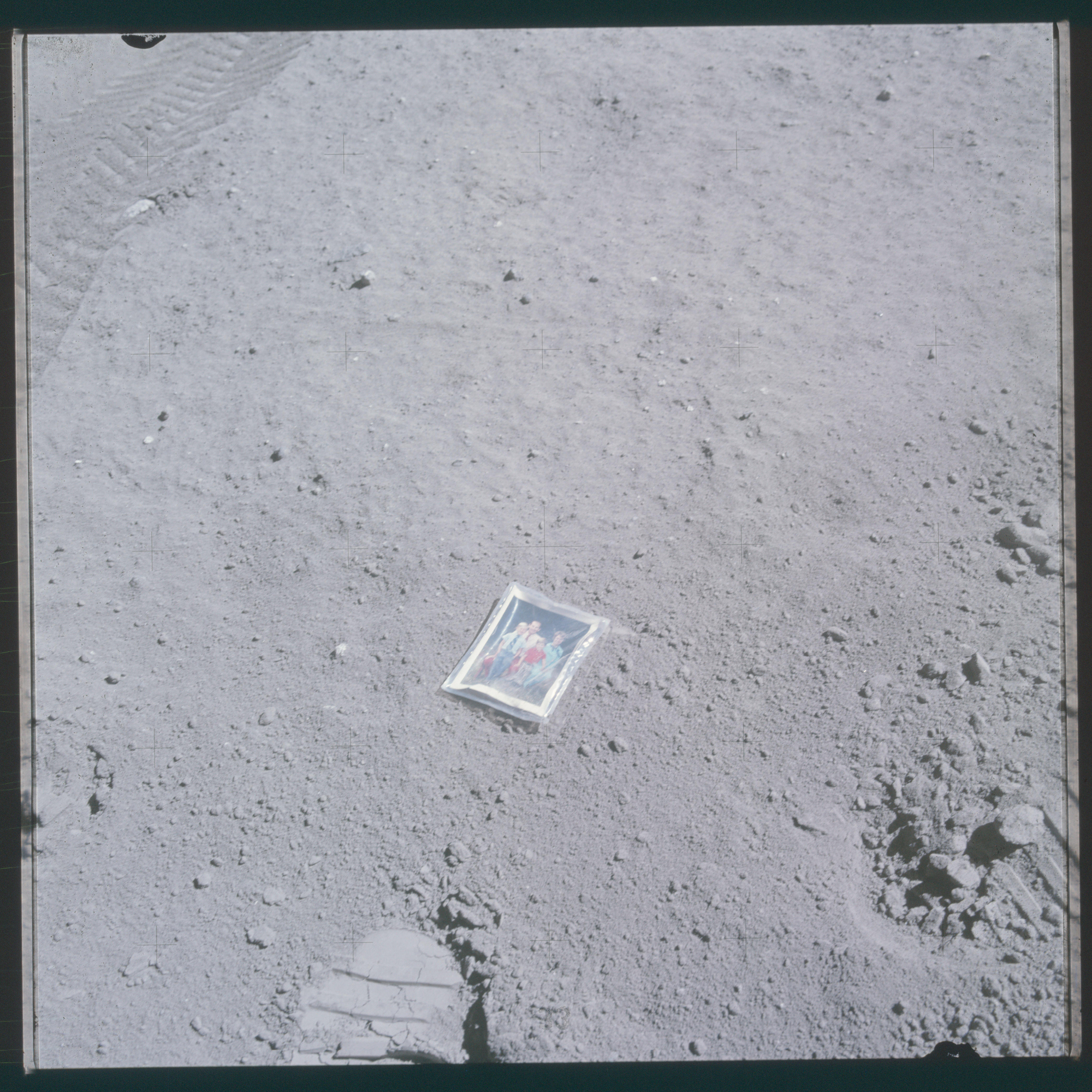

A family portrait

During the space programme my family lived in Houston, but we trained in New Orleans, so we were away from home all the time. Our boys were young at that time, five and seven, and I asked them, ‘Do you guys want to go to the moon with me?’ ‘Yeah Dad, that’d be great!’ they replied. So I said, ‘Well, we need to do a photograph.’ And so we took a picture and I got permission to take it with me. I took that photograph onto the moon and on the back of it I had written, ‘This is the family of astronaut Charlie Duke, who landed on the moon in April 1972’, and they signed it. So the photograph is still on the moon! Actually, the picture of the picture still survives. The original that was on the moon is ashes now.

A whole lotta shakin

The Saturn V was a tremendous ride, a lot of shaking, but I didn’t remember anyone telling me it was supposed to shake, so I got a little nervous. John Young (it was his second flight on a Saturn V) said, ‘Way to go Houston, it’s so calm’, and my heart’s pounding. When I got back I asked what my heartbeat at lift-off was. ‘You were excited, it was 144 per minute.’ I asked what John’s was at lift off. They said, ‘His was 70.’ So you can see who the calm one was on the whole flight! But it was really a wonderful time, from lift-off to touch down.

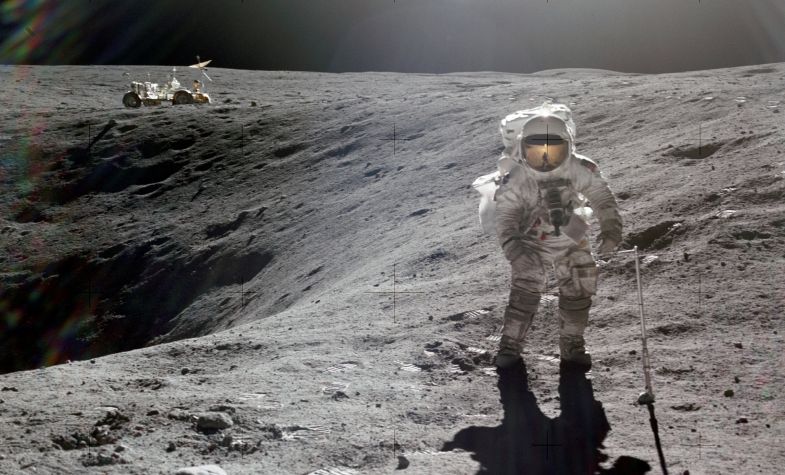

View from the top

Looking back at Earth, you can see the whole circle. The only people who have done this are the 24 men that went to the moon on Apollo – the space shuttle and other astronauts in orbit, they see the curvature but not the whole surface. It’s a unique experience to see Earth in all its colour, just hung in the blackness of space; awe-inspiring and breathtakingly beautiful. Looking down at Earth, you don’t see any people or civilisations or countries, there’s just the Earth, so you do get this impression that they’re all down there, we’re all together. It wasn’t a time of thoughtful reflection though, you’re more focused – at least I was – more focused on the operation, you don’t want to make a mistake. You don’t stand on the moon pondering; you’re so busy. You’re just looking at all these rocks and what’s over the next hill. It’s an operational feeling, but you’re having fun doing it.

Coming home

Returning in Apollo, we had to be in what we call a quarter, about a four-degree wedge, to intersect the Earth’s atmosphere. If you’re too steep, you will burn up on re-entry. If you’re too shallow, you’ll bounce out. We hit the atmosphere at about 26,000 miles an hour and started getting flashed outside as we ionised the upper atmosphere and quickly that just turned into a big fireball as we plunged in. I was the timekeeper, so Mission Control said ‘re-entry starts here, start your watch and when it gets to this time, if the computer doesn’t roll over, inverted, and pull you back into the atmosphere, you roll over and take over manually’. So I started my stopwatch and I’m watching outside with all of this blazing flame – it was very comfortable inside. I counted like one second, then two seconds, I was going to say to manually take over, but at about that time the thing flipped over upside down and we went back into the atmosphere. It really was a ride. It wasn’t shaky at all, just brilliant fire outside and acceleration that had built up faded away. Then at 23,000 feet the parachute sequence started and at 10,000 feet the main parachute started to deploy. I was looking out the window and I saw a helicopter fly by, so we knew we were close and we had splashed down. It was a great experience. What an ending to a great adventure, this fireball re-entry.

Timekeeping

I’ve been wearing Omega since 1969 when I got into the space programme – in ’66 Nasa gave me one to wear, to get used to it – and to still be associated with it and in great company is really a great privilege for me.

Return to the moon

Well, I have been lobbying for a return to the moon for over a decade. I think it’s a great place to build a science station and learn how to operate in deep space for extended periods of time. There we could gain experience of the systems – what we would need to survive on Mars – and it’s a good learning place. It’s near enough where you can get help from Houston; you can get re-supplied, stuff like that. You’ve got to have confidence in your systems when you go to Mars because there’s no re-supply. You’re on your own, buddy. So it’s got to work and you’ve got to be able to prepare those systems. I think you can learn to do all of that on the moon.

Space fact

Since 1965, the Omega Speedmaster has been the official watch for every piloted Nasa mission, and was worn by both Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong when they became the first men on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969. It is the only piece of equipment that has been used in all of Nasa’s piloted space missions, from the early days of Gemini to the International Space Station programme of today. Every astronaut of every nationality is now issued with two models: a mechanical Speedmaster Moonwatch for EVA (extravehicular activity) and a digital Speedmaster X-33 for use in-spacecraft. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, there is a gold version of the Speedmaster that replicates a model made to commemorate the event in 1969. That edition was restricted to 1,014 units and the new edition has the same number. It also features a piece of lunar meteorite on the caseback to represent the moon.