WORDS

Nick Smith

Humans have been fascinated by the idea of life on Mars ever since we discovered the Red Planet. The concept of little green men is a staple of 20th-century pulp sci-fi, we’ve imagined a face in its surface topography, while in the 1970s, on the back of the Cold War ‘space race,’ musicians – notably David Bowie, but there were plenty of others – speculated on the question to the accompaniment of squelchy synthesizer soundscapes. But we’ve never investigated the practicalities of what it would be like to actually live there. That’s because, says American writer, journalist and almost-astronaut Kate Greene, we’ve always been more preoccupied with the technicalities of how to get there. The rockets. The engines. The fuel. The computational orbital mechanics.

Greene is one of the few people on this planet qualified to pass comment on the subject with any authority. Having lived, slept and worked in a simulated Martian environment for four months as part of Nasa’s first Hi-Seas mission, she has gained an insight into what exploring our neighbouring planet might be like. And she’s gathered her thoughts together in her latest book – Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars – that has been eight years in the works. ‘The mission was in 2013,’ she says, ‘but it took me a long time to make sense of what happened.’

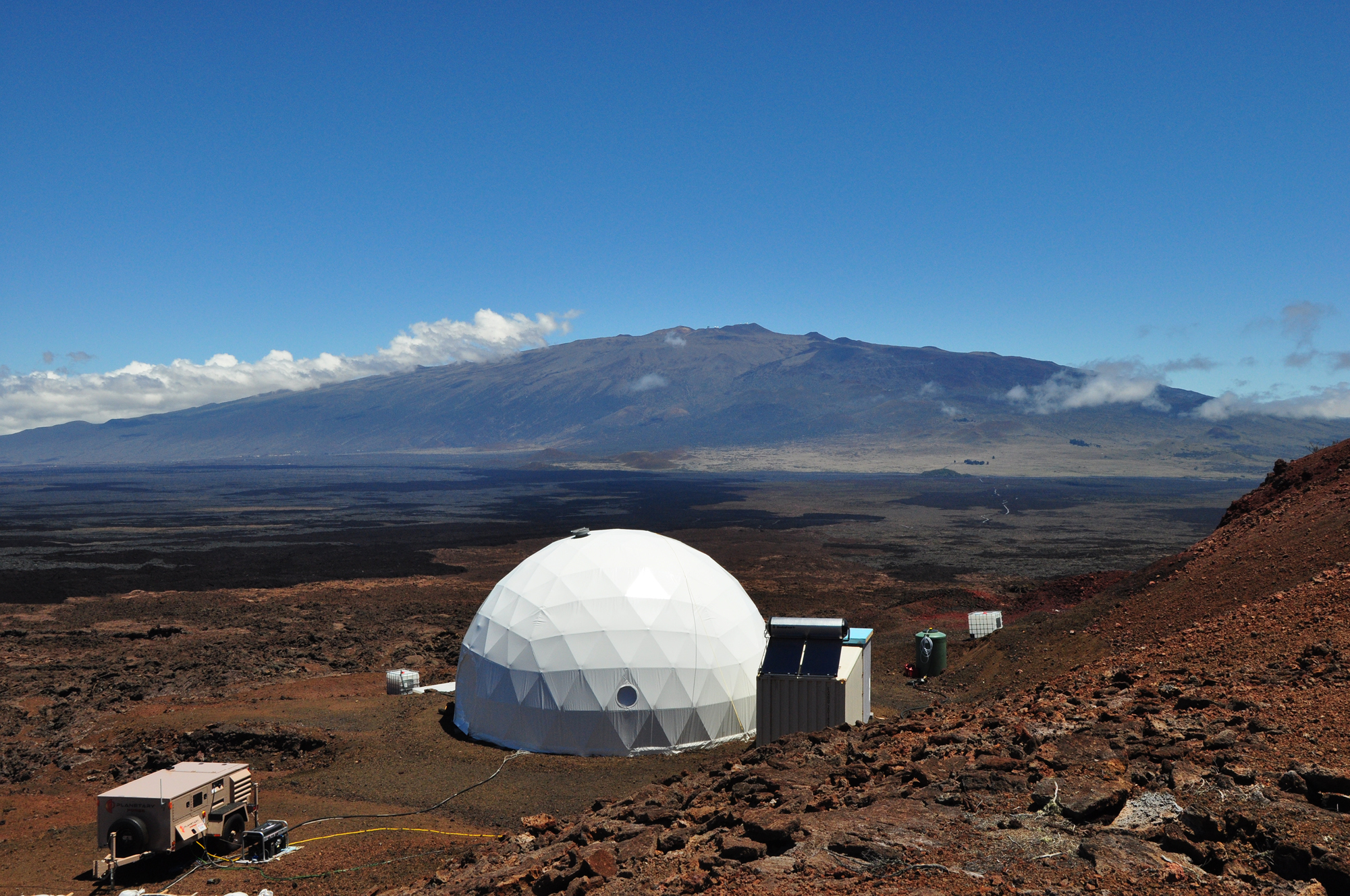

On the surface, at least, the ‘analog’ (as the astronauts term this type of training) looks easy enough: you pass a stringent selection process (Greene fought off 700 candidates for her berth on the mission), then go and live in a geodesic dome located on the distinctly Martian slopes of Hawaii’s Mauna Loa volcano in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Look a little deeper and the science masks months of boredom, isolation, repetition and irritation.

Greene is not what you might call a typical astronaut. These days, the former laser physicist and expert on ‘Big Data’ is more likely to describe herself as a poet than a tech nerd. This may seem light-years from the traditional hero image of space explorers of the 1960s, when astronauts on the Apollo programme tended to be clean-shaven, all-American, 30-something white men with engineering or military backgrounds, preferably both. ‘You can see why,’ says Greene. ‘Back then Apollo’s mission was to get to the moon, so the astronauts were part of the process, part of the engineering. You only had to survive for a few days, and so it was all about efficiency.’ But going to Mars is different. With the round trips potentially taking years, simply tolerating the conditions while getting the job done needs to make way for ‘quality of life for the astronauts. You’re going to be away from home for a long time, and so you’ve got to think about things like your mental well-being and what you’re going to eat.’

Life on the volcano wasn’t a typical Hawaiian vacation, says Greene. Perched 8,000 feet up on a red rocky surface, her existence, ‘was very Mars. We had limited electricity and water, zero access to fresh fruit or vegetables. We could only leave the dome wearing bulky, cumbersome space suit-like outerwear.’ Stripped of electronic devices and social media, reduced to bathing with wet wipes, breathing recycled air and living without real sunshine, life on Mars was rudimentary and challenging. ‘Our sole regular contact with Earth was through email. Since Mars is extremely far away and photons can only fly so fast, our email transmissions were delayed by 20 minutes each way to mimic the communication lag to be experienced by Martian explorers.’ Despite which, Greene tells me from her tiny apartment in New York, ‘It was easier to cope with than the Covid lockdown thing. In space you know the physics of how you’re going to die,’ she says, referring to the strict protocols for throwing a fellow astronaut ‘overboard’ in mission-critical scenarios. ‘All this,’ she says waving her hand vaguely at the Big Apple, ‘is kind of mushy. It doesn’t make any sense.’

The Hi-Seas ‘analog’ was just that, says Greene. A simulation in which she always knew that there were never going to be the sort of life-or-death scenarios that could face astronauts at least 30 million miles from home (the exact distance between Earth and Mars varies wildly with time, as they are on different orbits around the sun). She never found it particularly difficult to get on board with the idea that she was an ‘almost-astronaut’ on Mars, and ‘things got pretty normal quite fast, though of course there’s really nothing normal about six adults making believe they live on another planet’.

‘Life on Mars changed me,’ says Greene, remembering her profound adjustment issues on her return to Earth. Loud noises startled her. It took days to get used to the breeze on her skin again. It changed the way she thought about space travel, her life on Earth and other people. ‘I never saw with as much clarity as

I did in those first few weeks immediately after the mission ended.’

Once Upon a Time I Lived on Mars by Kate Greene (£14.99, Icon Books)