Words

Charlie Teasdale

For anything aged and sartorial, the first port of call should be Hardy Amies’ 1964 book, ABC of Men’s Fashion. Thanks to the couturier and tailor’s mordant wit and renowned bluntness, we can’t be sure that he was a hit with everyone in London, but his knowledge of men’s clothing and its rules was undeniably vast. Kindly, Amies took the time to jot it all down. Concerning stripes, he was characteristically definitive.

‘Stripes do not look well on every body. It is fallacious that they disguise irregularities of physique, either of height or width; their very conspicuousness probably achieves the contrary. On a well-proportioned man they can appear distinguished.’

Despite his reservations, however, Amies also stated that, although stripes had been out of the ‘front line’ of fashion for some time, he thought they were ready to make a return. He may have been right, but it’s safe to say that his prophecy has borne fruit in the autumn/winter 2017 menswear collections. In all likeliness, he was right back in the 1960s, and he’ll be bang on the money in 40 years’ time, too. Like a stopped clock, every look is in-trend twice a century.

‘Designers putting pinstripe pieces out now are more concerned with subtlety, and rightly so’

Over recent seasons, threads of commonality in men’s clothing have included souvenir jackets (light, elaborate bombers), chunky lace ups and dusty pink, or ‘Millennial’ pink to be more precise. This season, among corduroy, graphic slogan knitwear and the colour yellow, is pinstripe, or variations thereof. But perhaps before we discuss where the motif is now, we should consider how it came about.

‘Pin or chalk stripe is one of the rare cloths that has its origins in urban tailoring rather than country and equestrian,’ explains James Sherwood, author of Savile Row: The Master Tailors of British Bespoke. ‘Striped cloth becoming the uniform of City gents at the turn of the 20th century – indicating which financial establishment a chap worked for – was led by royal protocols of dress. Both King Edward VII and his son King George V favoured black frock coats for town worn with pinstripe trousers. Black morning tails with pinstripe trousers became the form at the races after the 1910 “Black Ascot” when the country was in mourning for King Edward VII. Pinstripe thus became the highest form of formal day dress for men.’

That bank theory is widely matched – although why a subtle stripe on a man’s trousers was the best way of determining his employer is unclear – and by the prosperous bull years of the 1990s, it was the uniform of financiers on the other side of the Atlantic too, immortalised (and perhaps critically wounded) by the likes of Gordon Gekko, Patrick Bateman and Jordan Belfort. However, there are those who will argue that the thin vertical stripe was worn at the more casual, sporting end of the spectrum long before it was adopted by young masters of the universe. As Austin Mutti-Mewse, author and archivist at Kent & Curwen (or ‘the history man’, as co-owner David Beckham calls him) points out, ‘I know that Charlie Chaplin was someone who wore pinstripe very early on. He felt it looked more modern than the suits his contemporaries, such as Douglas Fairbanks Jr, were wearing’.

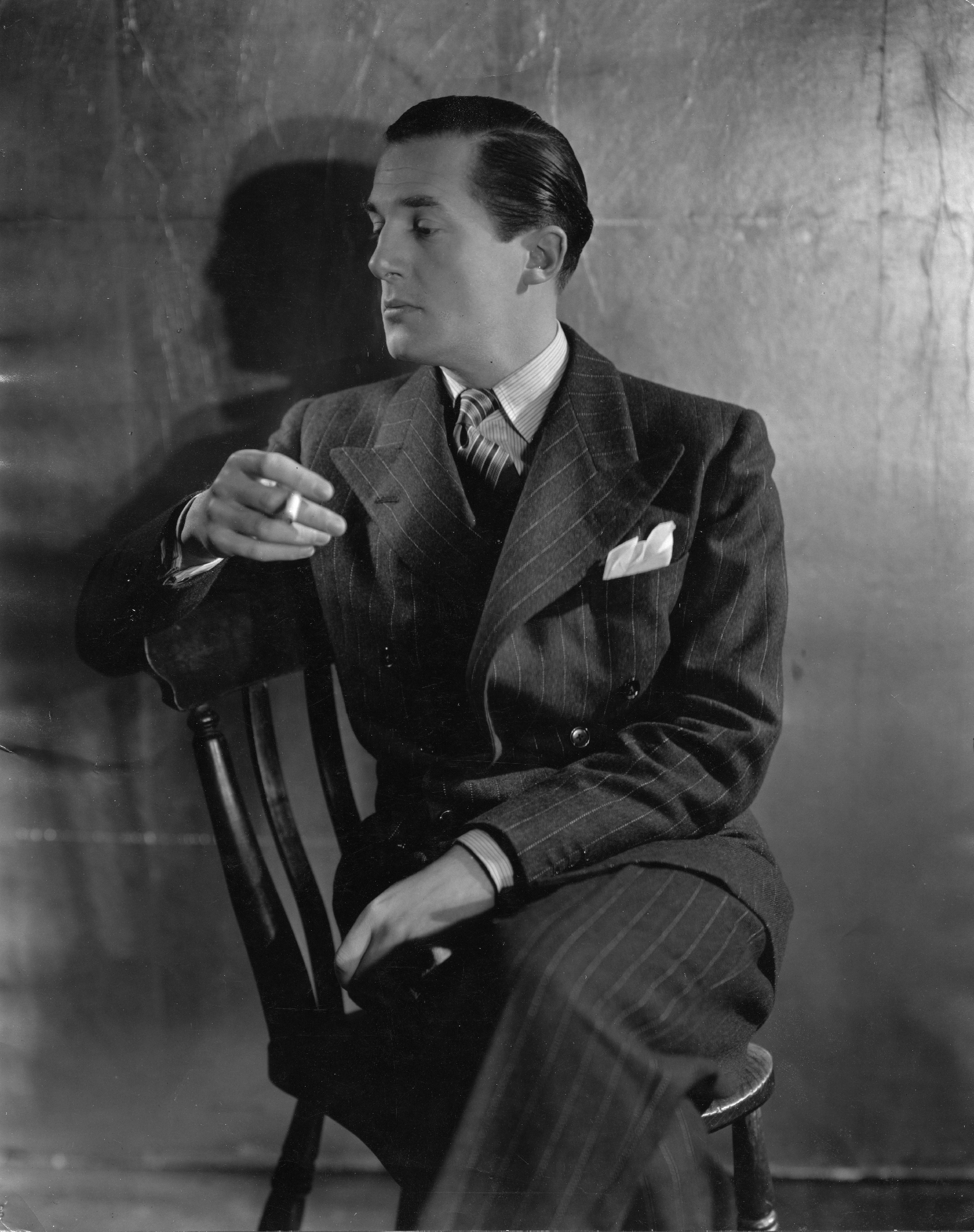

So, while stony-faced accountants were schlepping into the City from the suburbs in the company stripe, Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart and Johnny Weissmuller were jigging around Tinseltown in theirs. But that’s not to say the British 20th century was devoid of stylish exponents. Winston Churchill perhaps wore it best – or at least most memorably – during an inspection of Hartlepool’s coastal defences in 1940. His three piece, made by Henry Poole & Co of Savile Row, using cloth woven by Fox Brothers & Co, formed part of one of the most enduring propaganda images of the war, although the cigar, spotted Turnbull & Asser bow tie and Tommy gun certainly helped.

Keen-eyed sticklers will note that Churchill’s suit was in fact chalk stripe, rather than pin. The difference is that the latter is a series of individual dots, while the former is made up of wider, softer stitches, giving the impression of a line left on the cloth by the tailor’s chalk. Whereas pin is always thin, the thickness of chalk stripe can fluctuate, and many tailors and designers have taken this opportunity for subversion over the years. In the 1960s and 1970s, disruptive Savile Row tailor Tommy Nutter was of that vanguard, sculpting striped suits for the likes of Mick Jagger, Elton John and the Beatles. Later the Cool Britannia tailors, including Richard James, Timothy Everest and Ozwald Boateng, continued the anti-establishment spirit into the 1990s, and five or six years ago men went through that odd peacocky stage – all tweeds and winkle-pickers and twiddly moustaches – which briefly brought stripes to the fore once more, but thankfully that died out.

In these recent movements, the emphasis was on drawing attention, whereas designers putting pinstripe pieces out now are more concerned with subtlety, and rightly so. ‘Pinstripe will always have a place in tailoring,’ says Danny Ching, senior designer at Hardy Amies, ‘but by wearing more relaxed silhouettes and softer shoulders on your suits you can alter the formal look of the pinstripe dramatically. Additionally, by styling pinstripe tailoring with casual pieces like jersey or knitwear, you create an entirely new look.’

As its founder (sort of) predicted, Hardy Amies is once again pushing stripes to the fore, but it isn’t the only one. Jason Basmajian’s third collection at Cerruti is peppered with stripes, including a particularly louche peak lapel suit, with wide-legged trousers and a matching collarless shirt. It’s chicer than it might sound. ‘This season I liked mixing up the scales and dimensions,’ says Basmajian. ‘As well as using new fabrications: linen, cotton blends, wool/silk, which give a more relaxed mood to traditional pinstripes.’

Elsewhere, pin and chalk stripes pop upin collections from Pal Zileri to Acne and Canali. In tailoring, such as that from Brunello Cucinelli, traditional charcoals and blacks have been eschewed for deep blues, and are to be worn with battered chambray shirts or dusty camel knits. The big tip is Sandro. The Parisian brand has striped wide-legged trousers, oversized, square-hemmed shirting and boxy, fat-lapelled tailoring, which is best worn with white socks and white tennis shoes. Sur la Rive Gauche, ideally.

Should you choose to insert stripes into your current wardrobe, it might be wise to keep it understated. If it’s a suit, forego the power tie and contrast-collar shirt for a roll neck; you wouldn’t want to go full Wall Street. And if you’re keeping it casual, don’t allow the striped thing to be the focus. It should be the supporting cast; the Tim Robbins to your Morgan Freeman. A mustard-yellow overcoat, such as that from Ami, with a pair of softly striped Kent & Curwen trousers would do the trick. If all else fails, you can always channel Winston, or consult Mr Amies’ ABC.

Charlie Teasdale is style editor of Esquire’s Big Black Book