WORDS

Nick Smith

There can be few people who know the Amazon rainforest and its tribal people as well as Sue Cunningham. She’s spent decades with them, year in year out, becoming part of their way of life – ‘one of the family, really’ – often for months on end. And yet, her extraordinary career of high adventure deep in the farthest reaches of the Amazon rainforest is a far cry from her other life in smart and leafy south-west London. ‘I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve been to the Amazon over the years’, she says. ‘Literally hundreds.

Along with her husband, author and filmmaker Patrick Cunningham, she is the archetype of what we think of as an old-fashioned adventurer. She’s plucky and (on the surface at least) fearless. She gets to places that other people can’t. But more importantly perhaps – and the secret of her success as a photographer – she gets to know the people. With her every visit to the Amazon, the genuine mutual respect and trust between her and the people of the Amazon increases. They call her Nhogogo or ‘the sound of the waters’, just one of her tribal names that Cunningham says is in honour of her mellifluous voice – ‘at least, I hope so’. She’s photographed the tribal people repeatedly over the years, watching them grow, raise families and become elders. She first photographed Ta’Kire Kayapo from the A-Ukre village in the late 1980s when protesting against the building of a hydroelectric dam in the forest, and most recently took his portrait last year. Her first meeting with Kayapo was also when she met the late environmental campaigner Anita Roddick and also Sting, who supports Cunningham’s work to the extent that he wrote the preface for her latest book Spirit of the Amazon: The Indigenous Tribes of the Xingu.

‘When I first met Sting, he was genuinely confused about all the attention being heaped on him for his work in the Amazon. He said, “I’m a bass player in a band, and yet everyone is looking to me for wisdom about this stuff ”.’ It was a bit cheeky of me to get him involved in the book. I just phoned him up and he said yes.

An undergraduate at the University of São Paulo where she studied cinema, Cunningham’s first assignments were gritty documentaries, looking at social issues in the neglected favelas or city slums. She says she’d go out into the field on assignment, get what she needed to fulfil her newspaper or magazine commission, and then, go as far as she could into the jungle. In those days, she says, there were very few westerners there. ‘You’d see the occasional rancher’s truck go by. People were reticent and would say, “What’s a woman doing here?” You’re in the middle of nowhere photographing an iron-ore mine and you’re up against some quite nasty people with guns in their belts.’

Often there would be a political or environmental issue in some far-flung region to shoot. ‘I photographed gold mining in the 1980s. Illegal gold. Mercury pollution. Belo Monte Hydroelectric Dam, third largest in the world, destroyed the river and many communities, and now isn’t working properly because of lack of water. Indigenous villagers found the level of their rivers reduced so they couldn’t fish or use their boats – their only form of transport – leaving them isolated.

Cunningham’s taste for adventure comes from her unorthodox childhood. Whisked away to Brazil from Putney by entrepreneurial parents who exported agricultural machinery, she dropped out of college after experiencing censorship under the Brazilian dictatorship, followed by her tutor who offered her a job, ironically, making propaganda films for the government. Cunningham briefly returned to England, where her husband Patrick gave her a ‘serious camera,’ launching her career as an investigative photojournalist.

Despite countless global assignments, it is the challenge of working in the Amazon that keeps calling her back. ‘It’s about self motivation. People tell me I’m naturally inquisitive, forthright and determined. Sometimes I have moments when I think “I can’t do this,” but then something pushes me forward.’ She then recalls how she met some Indians in the jungle, whose outboard motor had broken down. Cunningham took it into the ‘enemy camp’ of an iron-ore mining complex to get it fixed for them.

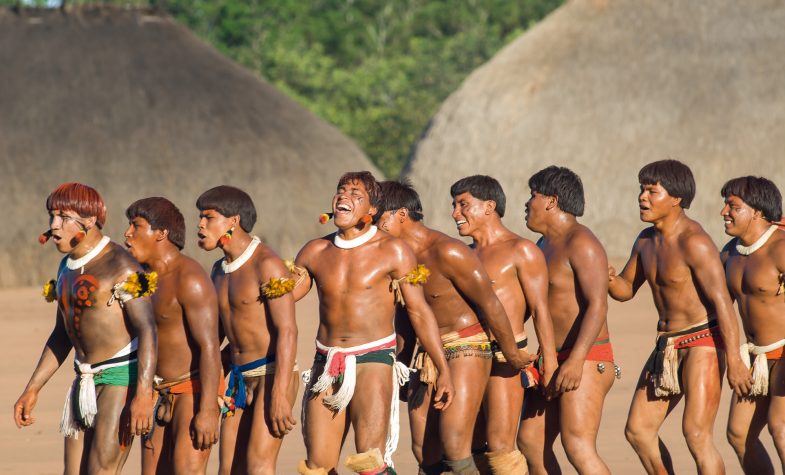

On her return, they were so grateful they took her to meet their people. ‘They took me in, fed me, body-painted me. That’s when determination turns into something bigger, when life grabs your soul. I saw them three years on, demonstrating against the Belo Monte dam on the Xingu river, and they said “oh, it’s you!” and so I stayed with them again. They were receiving death threats and people were throwing bottles at them. On the last day, the chief took his war club and he gave it to me, saying, “this is your fight too”. Ever since, whenever I feel confronted by anything, I feel their war clubs with me. I don’t need to find strength. It’s there behind me.’

Spirit of the Amazon: The Indigenous Tribes of the Xingu by Sue and Patrick Cunningham (£40, Papadakis), out now