WORDS

Ken Kessler

Kenny Rogers’ The Gambler kept running through my head. ‘You’ve got to know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em.’ Auctions are as much of a gamble as poker, but ‘No Reserve’ was not on my agenda when selling my own watches. And like the subject of Rogers’ 1978 country hit, I was in need of some sage advice.

The sales of the rarest Patek Philippes and Rolexes are, with a few exceptions, always headline-worthy, but vintage wristwatches are so hot at present that £1m-plus sales are almost commonplace. Seven-figure bids pop up with enough regularity to grab the attention of even the most staid of investment houses.

The records established by such horological unicorns are meant to be broken: last November, Phillips raised the bar for a wristwatch sold at auction with a unique Patek Philippe Reference 1518, which fetched a terrifying SFr9.6m (£7.3m). That, though, may soon be superseded.

The world’s watch-collecting community awaits the late-October sale in New York of horology’s holiest of holies: Paul Newman’s own, eponymous Rolex Daytona. His name unofficially graces a particular type of Rolex chronograph with specific dial colours and fonts; these now command anything from US $80,000 to $1.5m. This span is based on assorted influences ranging from famous ownership, to condition, to individual variations (eg the name ‘Tiffany’ on the dial). But Newman’s personal Daytona? The official estimate is $1m, rumour has two collectors talking up to $5m and those ‘in the know’ are betting on $7m-$10m.

With a near-vertical climb in values of late, owners of choice pieces are contacting the major houses to dispose of watches that are either surplus to their needs or simply too valuable not to sell now. And a seller’s market it is, because the new breed of younger, moneyed collector has to play catch-up with the previous generation of enthusiasts who own the very watches they want.

In my case, it’s the opposite – the burden of a 150-piece collection and the need to pay off a mortgage has lead me to my first time on the other side of the paddle. Amusingly, my collection’s roots are to be found as a buyer in the auctions of the early 1990s, when a Lemania RAF chronograph could be had for £250, or £500 in today’s money. The same chronograph is now an auction regular, consistently attracting bids of £2,500. My watch collection did better than my pension fund.

Thanks to a long-standing working relationship with Bonhams’ global head of watches, Jonathan Darracott, it was natural that I approach him to sell 21 pieces. But it wasn’t just the personal connection that steered me toward him: although the major houses – Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Bonhams and Phillips – overlap and can all claim record-setting sales, each has its own ‘persona’. Phillips, for example, now works with Aurel Bacs, the Elvis of auctioneers, and has no need to consider anything that will sell for under, say, £5,000. This ruled out most of mine.

Bonhams, which also offers seven-figure pieces, has two sales strata. The Bond Street auctions of fine watches command a low-estimate cut-off in the region of £5,000-£6,000. For less elevated timepieces, Knightsbridge includes estimates as low as £500-£600 – perfect for the majority of those with which I was about to part.

Because I was offering so many, as opposed to a typical client’s one or two which could be dealt with in a quick visit to Bonhams, Jonathan took a day out to visit me, to study the watches and take them to London. Despite nearly 40 years in the business, and perpetual contact with collectors, many of my preconceptions were undermined by Jonathan’s better grasp of what’s hot and what’s not.

It was an experience that mixed what I knew (eg the worth of the Lemania) with Jonathan’s detailed tracking of global price trends at a professional level. It provided a caveat for anyone about to sell watches: avoid temper tantrums and do some homework. Look online to form an idea of what your watch is fetching. Condition, rarity, the original box-and-papers – these create variations as extreme as one of mine, which I ‘know’ is worth £6,000, but Jonathan would only value at half that. This stage is one of negotiation, too, for the buyer’s premium.

The new breed of younger, moneyed collector has to pay catch-up with the previous generation of enthusiasts

We went through every piece with care. I was pleased to find my imagined reserve prices for 16 out of the 21 pieces matched Jonathan’s advised estimates. After the watches went to Bonhams for listing, I was emailed a contract with the lots itemised. A few disparities occurred between my expectations and Jonathan’s first suggestions, which necessitated a visit to the company’s offices.

An hour was spent with Antonia Bechmann, Jonathan’s colleague in the watch department, who went through the list with me. I decided to withdraw four watches, but for differing reasons: one to hold onto because the brand was predicted to go stratospheric next year; two because I wanted more than Bonhams wished to suggest as an estimate; one because its provenance was problematic.

Also, thanks to the meeting, I was able to add another watch, previously not submitted, because – in the interval between Jonathan’s visit and mine to Bonhams – another auction house had sold the same model for an exceptional price. I was keeping those words of Kenny Rogers in my mind.

This, too, affects buyers. Auctions are the most realistic ways to gauge what vintage watches are worth. The bidders determine the value, not some shopkeeper nor website with its own ideas of margins. Auction houses ensure that you’re not buying a stolen piece and may even advise on condition. If you’re of a nervous disposition regarding condition, though, stick with vintage-watch specialist retailers such as the Watch Club, David Duggan or Somlo Antiques, who offer warrantees.

One also needs to observe trends: Heuer chronographs from the 1960s and 1970s are so in-demand at present that their values will soon nudge Rolexes – no bargains here. Equally, the ever-ascending prices of Omega Speedmasters, military watches, 1940s/1950s chronographs and rare Rolexes or Patek Philippes are not trends: they are the norm. It’s unlikely the prices will ever drop. Do your research, consider watches other than the ‘usual suspects’, and you can snag a bargain. My tip? Vintage Longines, Tissots and Certinas are seriously undervalued, yet ooze horological heritage and style.

For me as a vendor, the next two months will be spent on pins and needles, my mind racing. Will my watches sell or stick? The one consolation: they’re my babies, and any which don’t find new homes will always have one here with me. I guess, for the horophile, watch love is eternal.

The London Houses

London’s houses hold wristwatch sales, of equal gravitas and successes, with the following guidelines:

Bonhams: Frequent London sales, with Knightsbridge for general watches and Bond Street for fine watches. bonhams.com

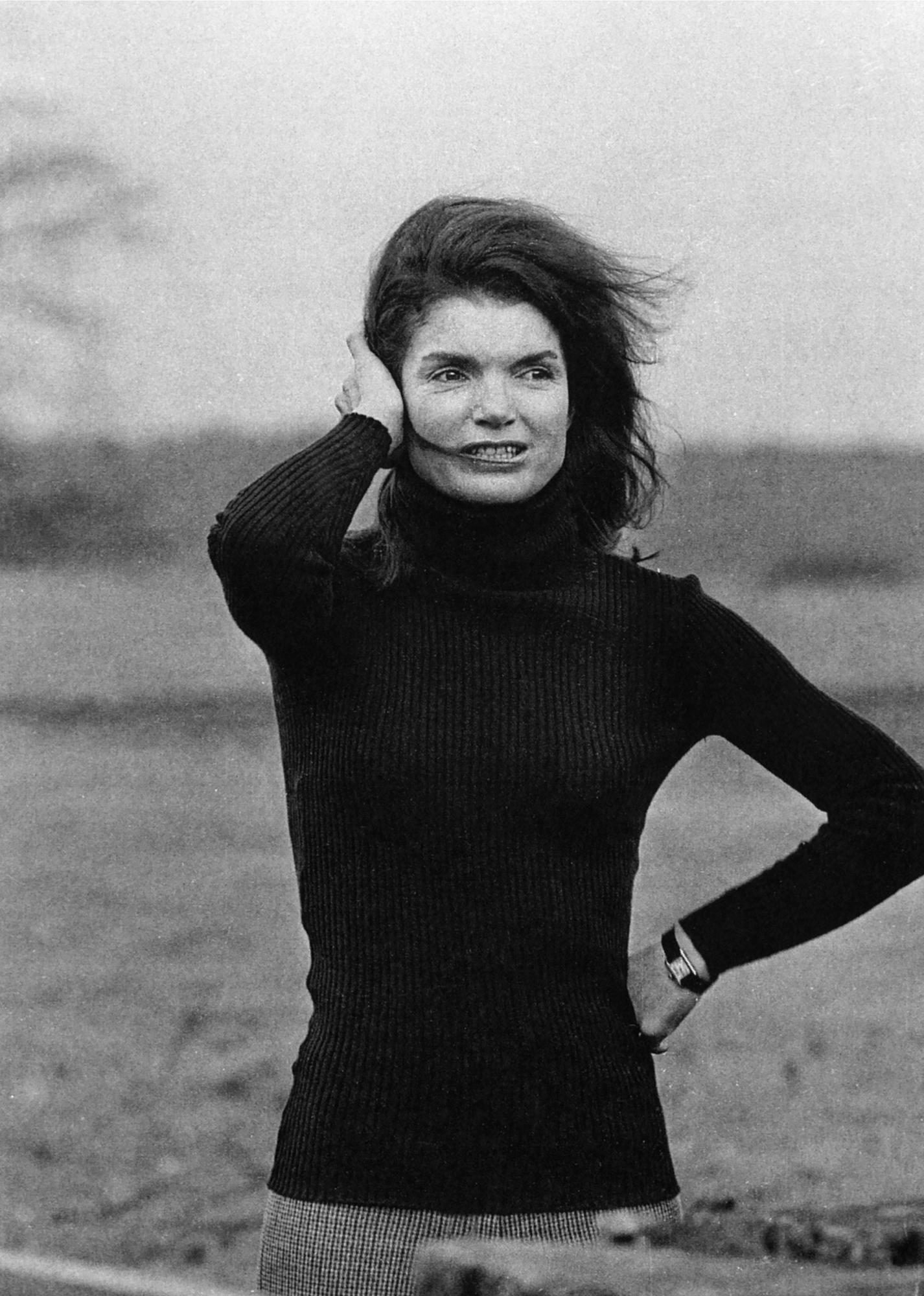

Christie’s: Recently sold Jackie Kennedy’s Cartier in NY, which commanded three times its estimate. Sales in Hong Kong, New York and Geneva. christies.com

Phillips: Holds themed auctions, for example, only Rolex day-dates, but watches must be truly exceptional. This is the house that snagged Paul Newman’s eponymous Rolex for New York. Their biggie is Geneva. phillips.com

Sotheby’s: Currently basking in the glow of selling legendary watchmaker George Daniels’ Space Traveller pocket watch for £3.2m in London. sothebys.com

Watches of Knightsbridge: Young upstart and a wild card. Bargains to be found, but also able to surprise, with fantastic results for military watches and 1960s/1970s diving watches. watchesofknightsbridge.com