WORDS

Alex Fraser

Omega has an enviable position among luxury watch brands. Fans have ranged from JFK and Gianni Versace, through to George Clooney and Prince William, and in terms of name recognition it is incredibly strong. But Omega is never seen as flashy. And very far from being a fashion brand. With second-to-none watchmaking credentials, Omegas are bought by people who know what they like, rather than those who want to show off. It’s this confidence in its own individuality that has contributed to it recognising for over a century that women want to be considered as customers in their own right. The Swiss brand is proud of its long heritage of making watches for women. And unlike some rivals, it has not merely shrunk the case size of its men’s collections to fit daintier wrists, but has, in fact, created some distinguished pieces for females over the decades.

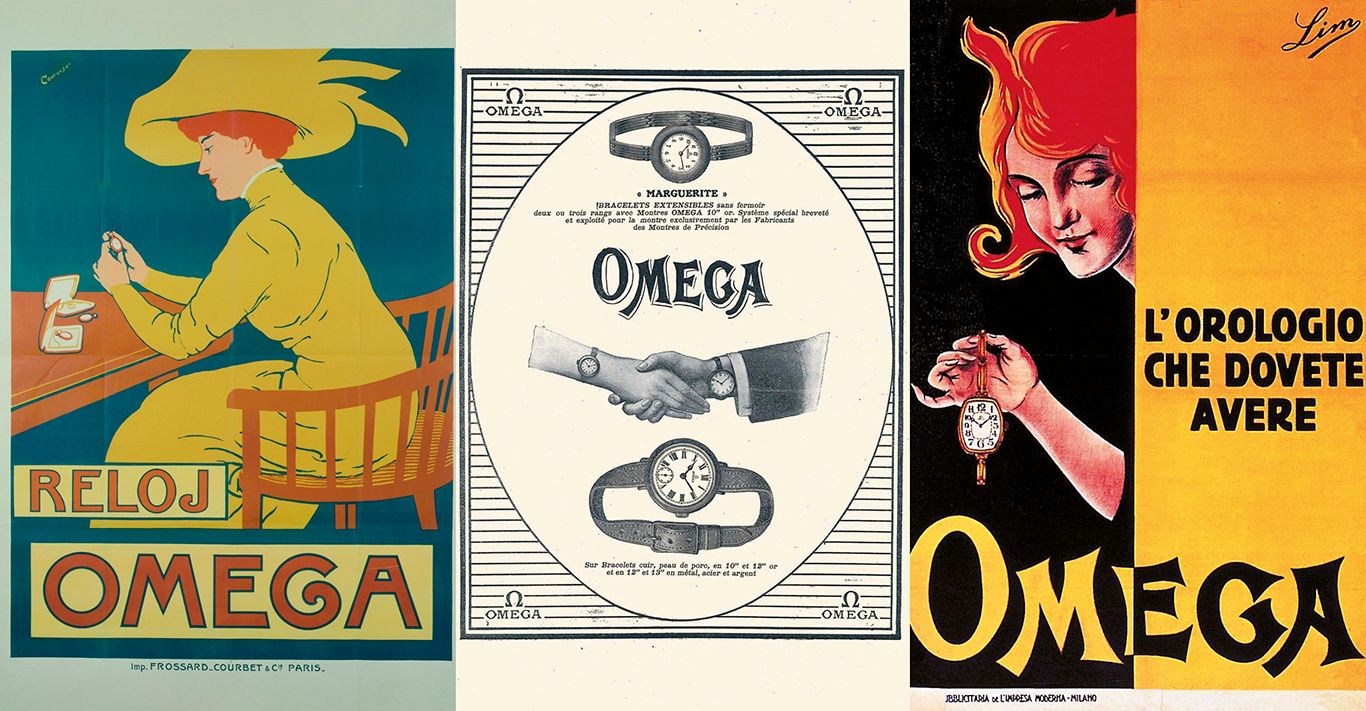

The 20th century was a defining era for women’s rights, and the history of Omega’s women’s watchmaking during that period reflects these changes in attitudes and style, keeping in step with women’s preferences. Two years into the last century, Omega debuted its first wristwatch for ladies. But even in 1902 it was in some circles seen as unseemly for a woman to look at her watch, in case it suggested – heaven forfend – she was bored. So the watchmakers also produced pieces – called “secret” watches – that looked like elegant jewellery, but hid a small watch inside.

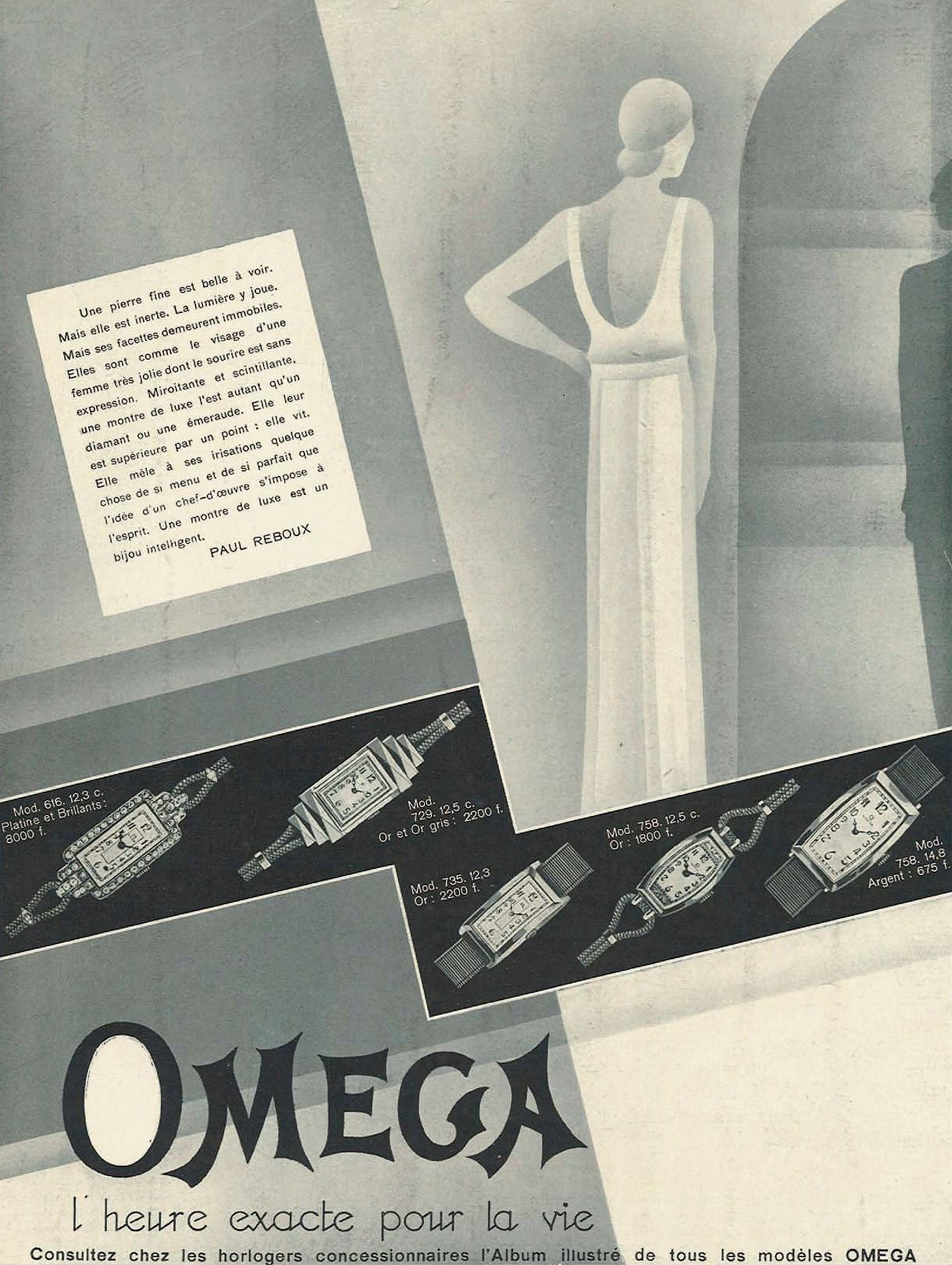

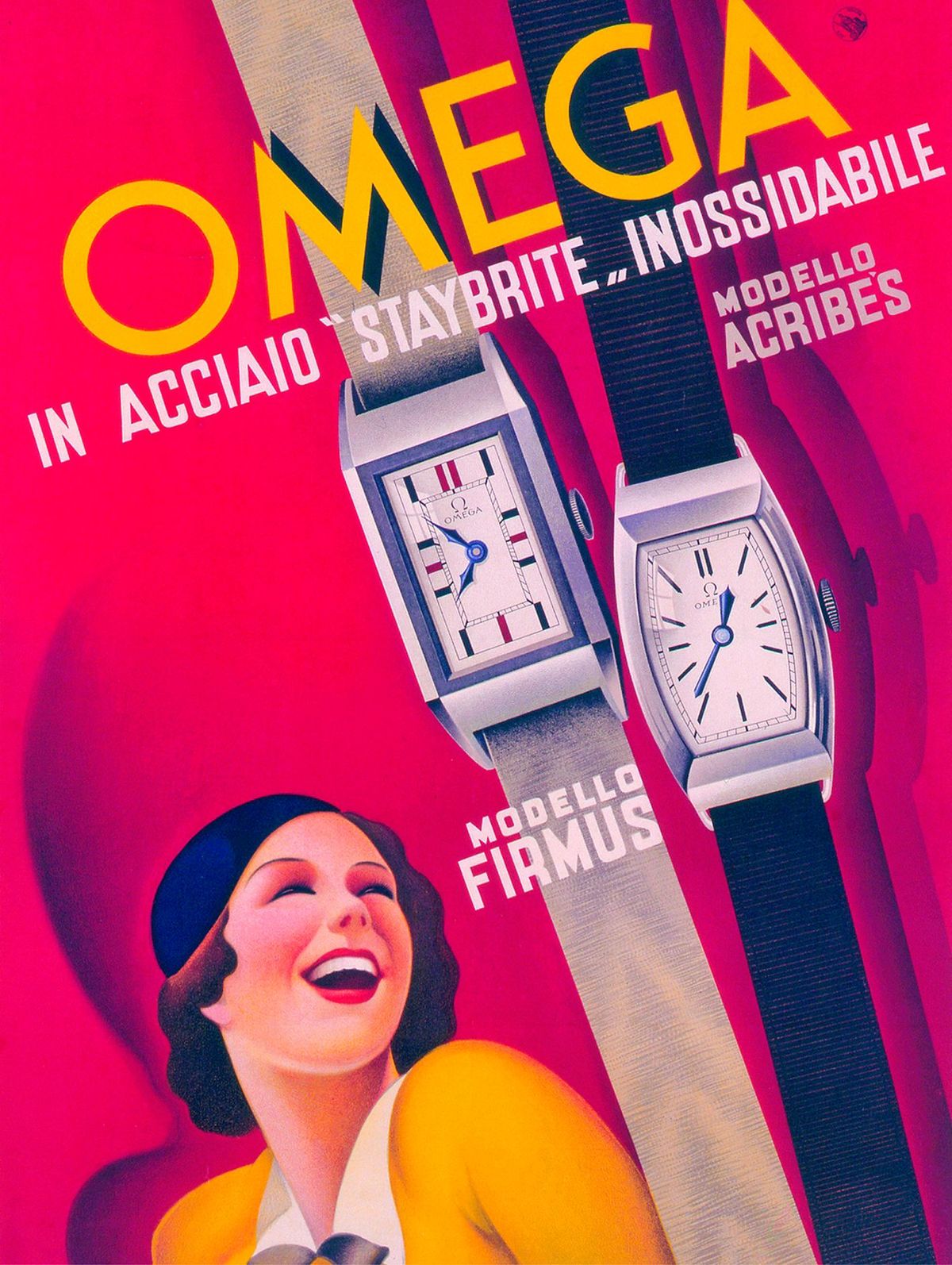

Omega’s women’s pieces really came into their own during the 1920s, as the Art Deco movement introduced rich colours with bold, simple, architectural shapes and pure lines. Reflecting the era’s new-found liberty and expression, a range of jewellery watches were designed. But they weren’t just pretty: it was understood that women were interested in the inside of their timepieces as much as the attractive exterior. Interestingly, more than 35 per cent of Omega’s advanced movement production was destined for women’s pieces around this time. It has been observed that in some cases women’s watches have required a finer and more delicate level of craftsmanship than men’s watches, to incorporate jewellery and tiny movements within a sleek casing.

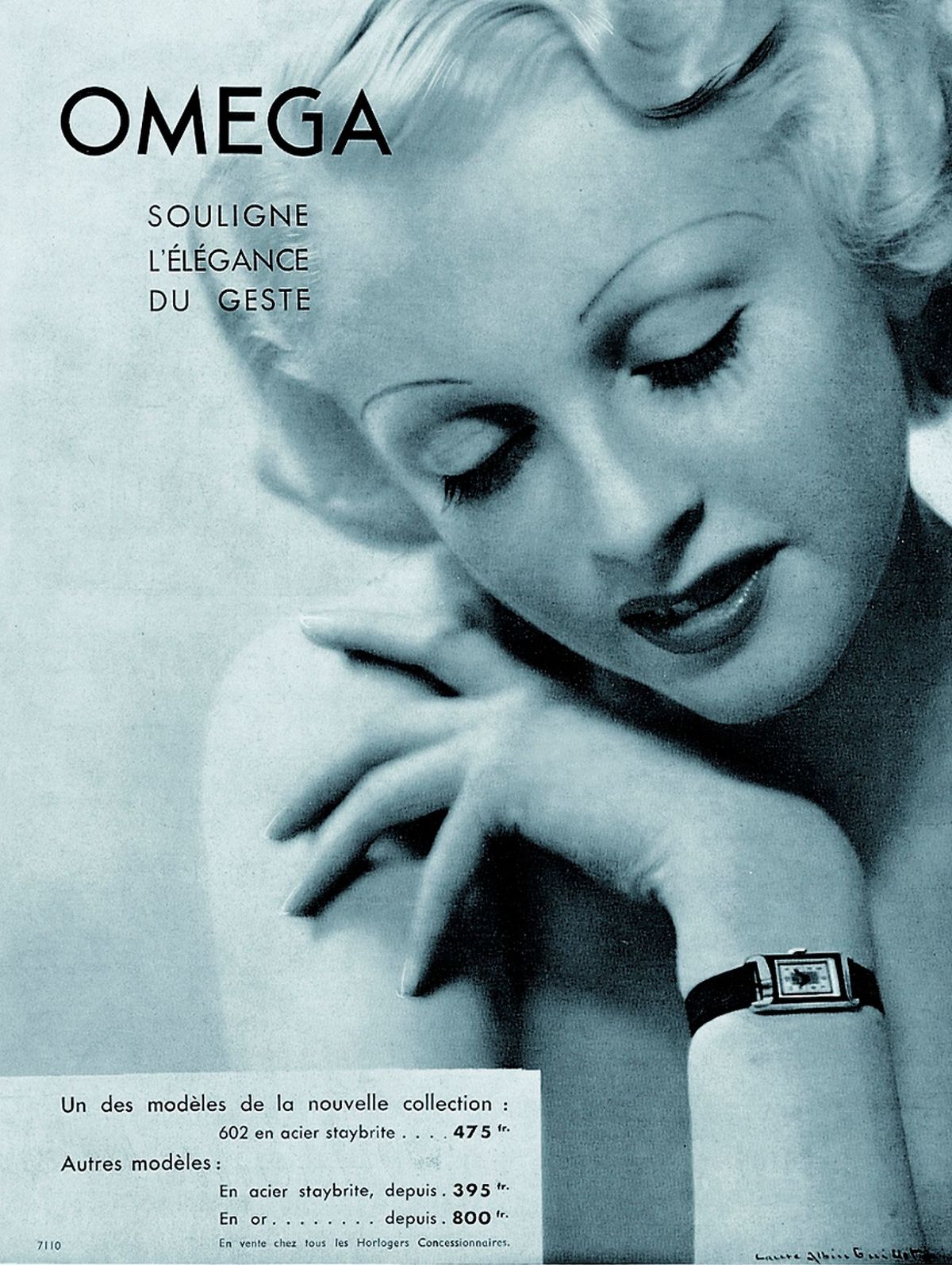

As attitudes and lifestyles evolved during the 1950s, the brand’s advertising stepped away from illustrating the typical stereotyping of domestic duties and innuendo – sometimes not even aimed at women at all. Instead, Omega ads embraced individuality and promoted a sense of style that aimed to depict each woman as unique, making a stand for elegance and personality. Now the brand made its strongest play for the female market by launching the Ladymatic. Created in 1955, it featured the world’s smallest rotor-equipped automatic calibre. Superior to anything else on the market, it was an instant sensation, melding advanced technology with beautiful designs.

Most recent examples include the Trésor, a classic design with modern sensibility, and currently the new Aqua Terra range, expanded to include some injections of subtle colour, taking inspiration from land and sea. All the models are fitted with Omega’s 8800 chronometer-certified in-house automatic movement with co-axial escapement.

In March, Omega’s travelling Her Time exhibition came to London, showcasing the evolution of its women’s timepieces and changing styles, looking at women’s watchmaking, from late 19th-century pendant watches, Art Nouveau and Art Deco jewellery watches, Mid-Century masterpieces and contemporary icons.