WORDS

Mark Hooper

ILLUSTRATION

Aistė Stancikaitė

In association with

Any attempt to summarise the philosophy of Japanese design will inevitably be riddled with apparent contradictions. How does one reconcile the dedication to tradition and heritage with the obsession for innovation and the ultramodern? Or the keenly felt influence of nature with highly developed consumerist society? Not to mention the emphasis on beauty in all things alongside the huge popularity of kitsch?

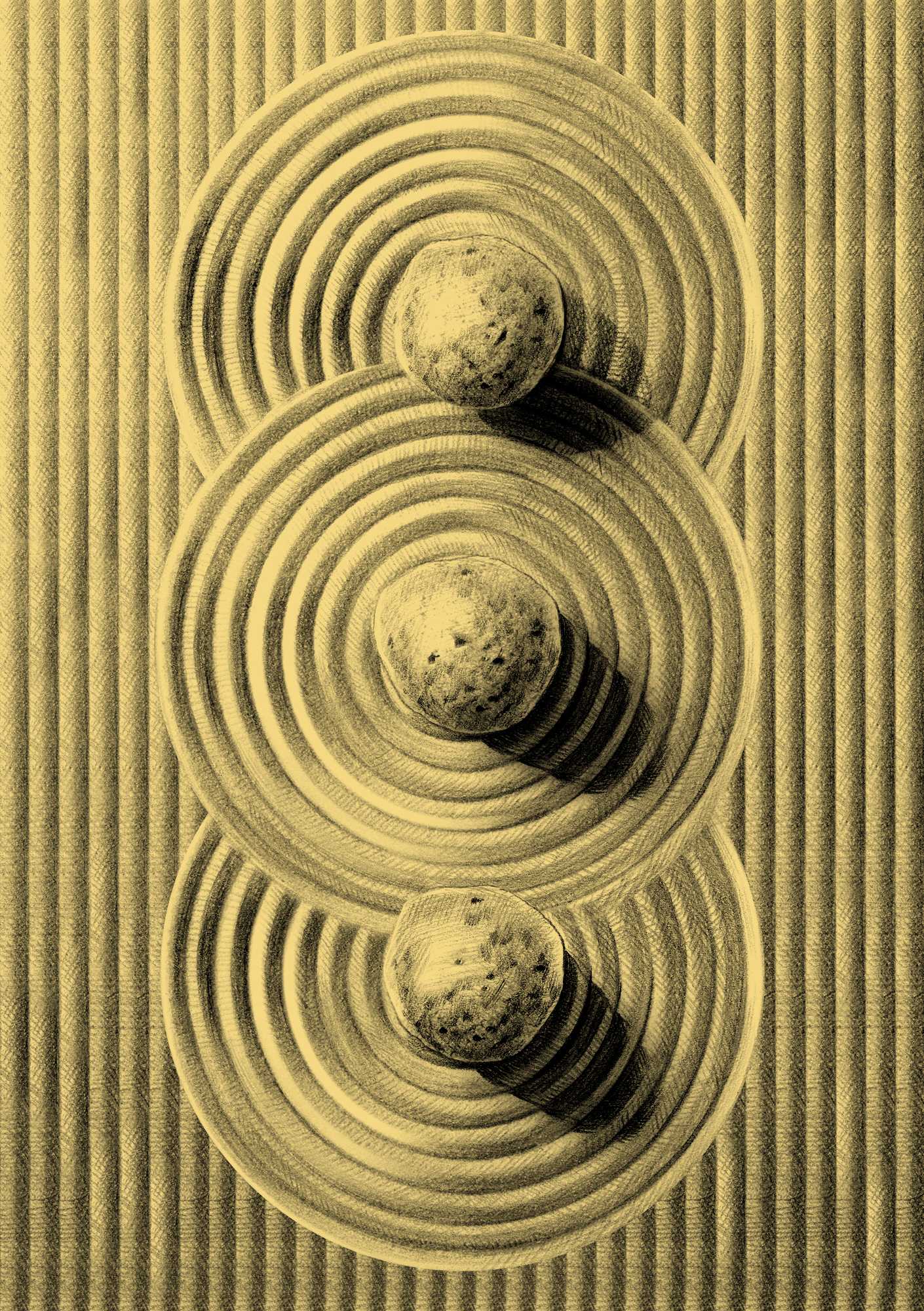

The smart answer is the simplest one: the question is wrong. In true Zen style, each of the above should be seen as aspects of the same whole. Traditions are born of innovation; what is now seen as part of one’s heritage was once the ultramodern; society is a part of nature; if beauty is in all things, it must also be in the kitsch.

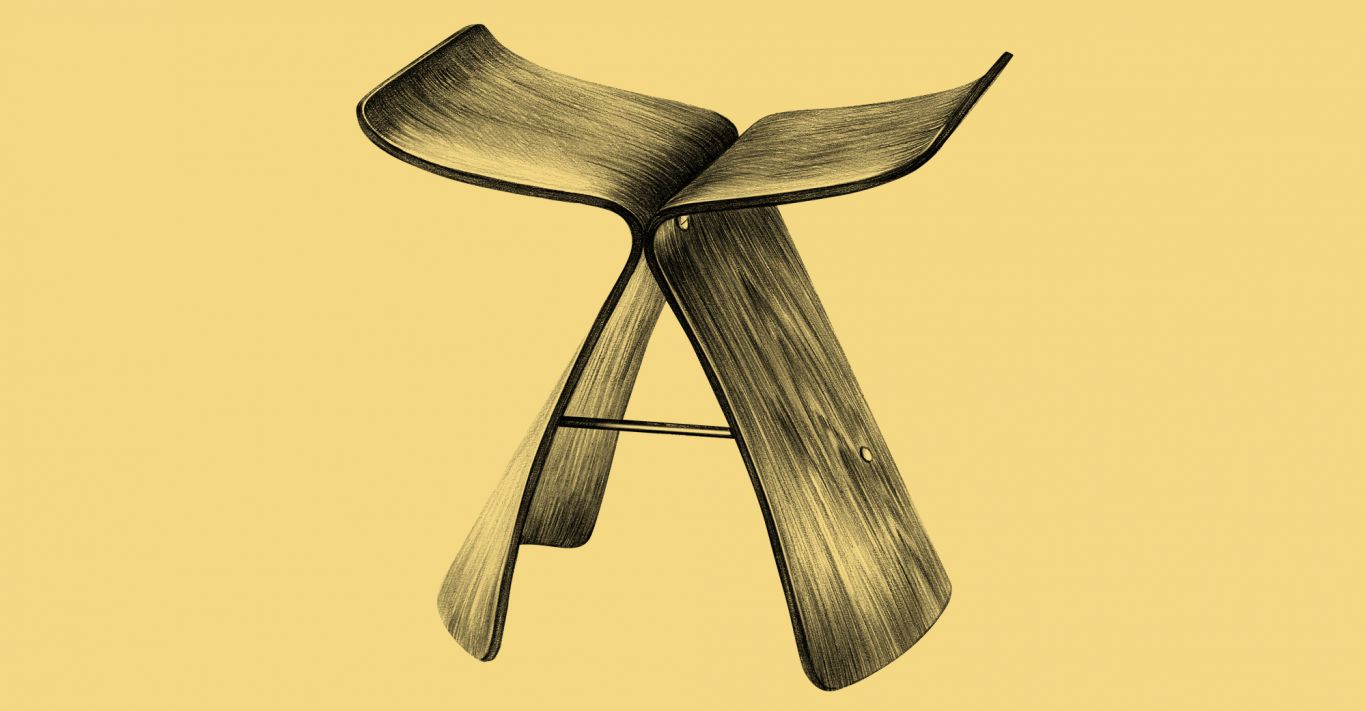

This holistic appreciation of the beauty in all things stems from the ideals of Shinto-Buddhism, but there are so many elements that the best we can do is to touch on some of the best known. Take, for instance, wabi-sabi: the beauty of imperfection, impermanence and incompleteness, which has captured the imagination of Western designers. Often interpreted as an appreciation of the handmade, where the lack of industrial machinery means the mark of the maker is clear: a lack of perfection becomes a thing to celebrate.

But of course it’s more complicated than that. Wabi-sabi itself is sub-divided into seven aesthetic principles that all need to be satisfied. These range from asymmetry (fukinsei) to simplicity (kanso). Even the idea of celebrating the beauty of transience differs subtly from Western interpretation: where the Romantic poets of the West might revel in the fleeting moment when a tree is in blossom, the wabi-sabi approach is to celebrate each stage – from bud to bloom to withered flower. In other words, the transience itself is beautiful.

So whether we are discussing architecture, product design or even pop culture, there is an understanding that aesthetics involves far more than the finished product. And while much of this stems from ancient philosophy, its vogue in design can be traced to a modern revival of interest that takes inspiration from the West as much as the West has been influenced by it.

Nature, art and beauty are all aspects of the same collective whole

Take the concept of the Unknown Craftsman – the title of the international bestselling book by Soetsu Yanagi (1889-1961), founder of the modern mingei or ‘folk craft’ movement and in many ways the Japanese equivalent of William Morris. Looking at everyday modern design classics – the baseball bat, the teapot, the tap – Yanagi pointed out that none has a clear designer. We don’t know who invented any of them, but generations of unknown craftsmen have perfected the design over the centuries. Absolute perfection has not yet been achieved, of course: as it is the process that is celebrated.

In architecture, the traditional and the new stand shoulder to shoulder in the crowded streets of urban Japan. From an outsider’s perspective, the embracing of modern architecture – the famous neon-festooned crossing at Shibuya, for instance – might seem at odds with a deep respect for history. But, unlike in the West, there is a culture for revival and rebuilding. The wood used to build Shinto temples is returned to the forests every 20 years, for example, as part of the cycle of nature. So if even the holiest shrines can be rebuilt from scratch, why not the incredible glass and steel structures of Prada and Comme des Garçons shops too?

The Japanese concept of beauty has always absorbed those of other cultures too. Since it was originally an amalgamation of different philosophies and religions – Shinto, Japanese Buddhism and Zen (which originated in China) – there is no contradiction with looking to the ideals of other cultures and new generations. Look at kawaii, a very modern concept of ‘cuteness’ or ‘adorability’ that is synonymous with Japanese popular culture and cartoon characters. It is typical of the Japanese approach to design that kawaii (its name derived from the phrase ‘face aglow’) is accepted as part of this elusive cultural concept of beauty.

This acceptance of the modern is what makes the Japanese design outlook so fascinating. ‘We have been good at emphasising the functional appeal of our products such as precision, superb accuracy and specifications,’ says Kiyomi Tanemura, head of the design studio at Japanese watchmakers Seiko. ‘I wanted to further convey to the world, the emotions and aesthetics we put into our work as designers.’ The designer Paul Smith, a keen ‘Japanophile’, has spoken with enthusiasm about how Japanese fashion is ‘more extreme in many ways than a lot of European design’, praising the creativity and bravery of the way in which each new generation chooses to dress. But it is also wrong to think of Japanese aesthetics as being removed from those of the West: Yanagi himself encouraged the parallels between his own thinking and that of the Arts and Crafts movement in the West.

But this isn’t solely a backwards-looking reverence for the way things used to be. Yanagi was equally as enthusiastic about 20th-century Scandinavian design as well as the work of Charles Eames – both of which were at the cutting edge of contemporary, modern aesthetic thinking. It is, instead, about an attitude and an approach that acknowledges every stage in the process of creating something that can truly be referred to as ‘beautiful’.

This interchange of cultural learning and a refreshing openness means that any unified notion of aesthetics is larger than simply a ‘Japanese’ concept. No distinction is made between truth and beauty, or between different categories of art: all bring us towards a connection with the infinite. Nature, art and beauty are all aspects of the same collective whole. Whether discussing music, art, architecture, interiors, film or product design, we can celebrate the skills and innovation of the people who create moments of aesthetic joy, but it is the creation and the sense of beauty it inspires that is paramount.