WORDS

Richard Holt

The organisers of the Olympic Games take pride in carrying on no matter what curve balls they face. Since the modern Games began in 1896, only three have been cancelled, when we were in the grip of world wars. Since then the Games have faced terror attacks and boycotts, not to mention endless dramas about whether facilities will be ready on time. Somehow, the Games always go ahead. And now we will get the first ever postponed Olympics, fashionably late and still calling itself Tokyo 2020, as if last year really could be rewound and played over. But no matter how difficult the journey has been, once the oldest and grandest of all sporting competitions begins, none of that will matter.

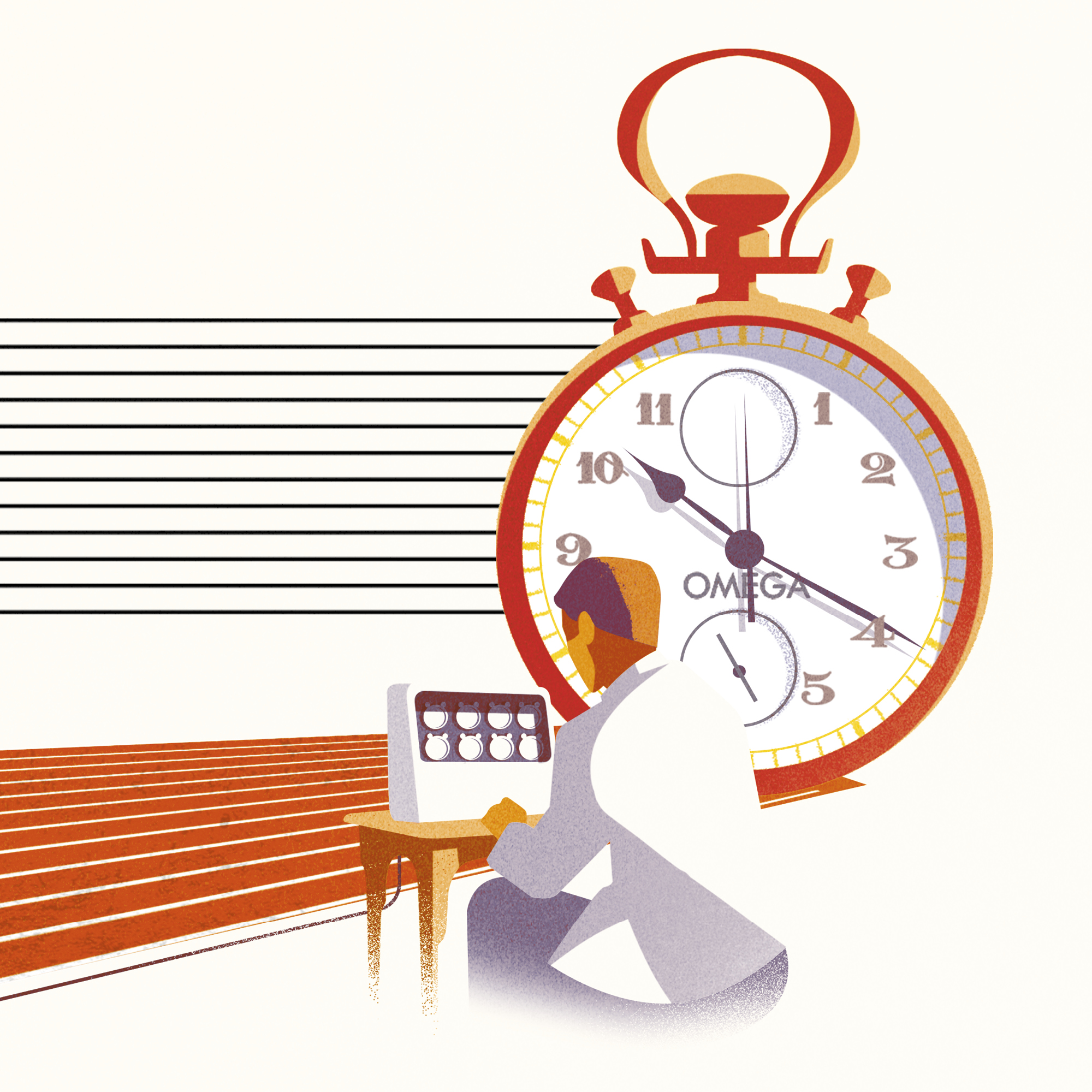

An athlete has precious few chances at Olympic glory and will fight just as hard for medals no matter how long it has taken to get there, or how many fans are allowed in the stadium. The fight for glory comes down to the finest of margins, so expert timing is crucial. Omega is the Official Timekeeper for the 29th time and will be ensure that not a single split second is missed across 339 events in 33 sports. When Omega first timed the Games, back in 1932, a single box of stopwatches was taken. This year, thousands of boxes containing more than 500 tons of specialist equipment – including 200km of cables and optical fibre and more than 400 scoreboards – have been brought to Japan from the Swiss mountains. Over the years human error has gradually been removed from the all-important decision over who wins gold, and new technology has played a vital role in the development of the Games.

1932 POCKET WATCHES

The Los Angeles Games of 1932 also took place under difficult circumstances, with the world in the grip of the worst economic depression ever seen. While several nations did not send any athletes, those that did make it were treated to a number of Olympic firsts. There was a purpose-built Olympic village for the first time, and a winners’ podium was used for the first time at a summer Games. It was also the first year that an Official Timekeeper was introduced. At the previous Games, officials used their own stopwatches. But in 1932 a watchmaker travelled from the Omega factory in Bienne by train and ship to LA with a box of 30 identical high-precision stopwatches that measured time to 1/10th of a second. Each night the watchmaker would take the stopwatches back to his hotel room and calibrate them before handing them back to race officials. Everything was done to ensure that the timekeeping was as good as the best technology of the day would allow.

1948 MAGIC-EYE CAMERA

When the Games returned in 1948 after a 12-year gap, host city London was still physically and economically battered by war and very little was planned by way of razzamatazz. The human cost of the war was huge, but the technological flipside was undeniable, as humans on the back foot made giant leaps in aeronautics, medicine and electronics. The London Games were big on austerity, but in technological terms it was a watershed, with Omega using its Magic-Eye photo-finish camera for the first time. The timer was started by an electronic impulse triggered by the starting pistol and stopped when a beam of light was broken on the finish line. Manual timers were still used as well but the new technology was legitimised by a razor-close finish in the showcase men’s 100m. The race was too close to call by hand and naked eye, but a winning-line photo was able to confirm a spilt-second victory for Harrison Dillard over US countryman Barney Ewell. Remarkably, it took years for officials to rely solely on electronically controlled timers, and hand-timers were used alongside right up until Tokyo 1964. But the arrival of the electronic era was exemplified by that famous sprint photo finish of 1948.

1968 SWIMMING TOUCH PADS

Timing swimming races presents its own unique challenges, as you cannot reliably use a beam of light to stop a clock in a pool when there is water splashing everywhere. In the 1960 Rome Olympics there was a big controversy when, due to discrepancies in hand-operated stopwatches, the runner-up in the men’s 100m freestyle officially swam faster than the winner. Video footage of the silver medal winner apparently touching the end of the pool first led to the Olympic Committee taking action to avoid a repeat of this awkward situation. Omega worked on a system that took seven years to develop, before being trialled at the World Championships and then getting its Olympic debut at Mexico City in 1968. Large pads, two-thirds immersed in water, were placed at the end of the swimming lanes, and when the swimmer’s hand touched the pad, an electronic circuit was broken and the clock stopped. Again, manual timing continued alongside for a while, but the touchpads won the day, and an updated version of essentially the same system will be used in Tokyo.

2010 ELECTRONIC STARTING PISTOL

The starting pistol spent more than half a century being a piece of old-world kit attached to the electronic network. From 1948, the gun was attached to an electronic timer so the blast from the gun started the clock. But athletes were still at the mercy of the speed of sound – the bang would reach the furthest athletes later than then nearest ones. We are only talking about a tiny amount of time, but in races where hundredths of a second are vital, such an advantage cannot be given lightly. This old-world slowness of the starting pistol was aggravated by a reality of the modern world. The traditional pistol was a modified firearm, and travelling through airport security with anything potentially loud and scary had become increasingly difficult. Once again, the Official Timekeeper was tasked with a solution to the old-school pistol, and the answer came at the Winter Games in Vancouver 2010. Omega’s electronic pistol eliminates the need for any gunpowder, and the very non-threatening red device starts the clock at the same instant that coordinated, simulated bangs are set off behind each athlete’s starting blocks. It does not guarantee every runner a good start, but at least the electronic starting pistol gives everyone the same chance.

TOKYO TECH

Accurate sprint times have long been a given at the Olympics. But timing has become about more than just a single measurement. There is now so much more in involved and in Tokyo things are taken to a whole new level. The most significant advance is in motion sensing and positioning systems. Where possible, athletes will be using wearable tech, tailor-made for each event. Triathletes, for example, will have an electronic chip in the shoe while running, on the wrist while swimming, and on the bike when cycling. The aim is to monitor every movement of every athlete and provide comprehensive real-time data. This will provide sport-specific insights for the host broadcaster, telling fans who is accelerating the fastest, jumping the highest or covering the most distance. But as well as entertaining spectators, crucially all data is available to the athletes and coaches, who can use it to make vital corrections to how they perform under the highest pressure. In gymnastics, pose detection is available to the judges if they want to check how cleanly a gymnast has moved through the air. And that is at the core of the timing mission. It is all about celebrating human endeavour but in doing so me must acknowledge that athletes move so fast, they are a blur for even the quickest eye.